One of the concerns about Medicare Advantage (MA) is that it doesn't serve sick beneficiaries well, motivating some of them to switch to traditional Medicare (TM). If true, it's an argument for maintaining affordable access to TM.

There's considerable evidence that it is true. The most recent (if you can call last summer recent) is found in a paper by Elizabeth Goldberg and colleagues. They examined Medicare beneficiaries 65 years or older between 2000 and 2012, a period during which enrollment in MA grew from 19% of beneficiaries to 28%. For each year, they classified a beneficiary as "MA" if enrolled in an MA plan in January of that year, and "TM" otherwise. Note, however, that it wasn't until 2006 that beneficiaries had to stick with their plan choice for most of the year (lock-in). Nowadays, they can adjust their plan choice only until mid-February. Prior to 2006, they could switch plans every month.

TM has no Part A (hospital insurance) premium and it's standard Part B (physician services insurance) premium is 25 percent of program costs, or $134 per month in 2017. The premium is higher for individuals and couples with higher income. Both parts include considerable cost sharing and both have an open network and impose no managed care-type restrictions on utilization. Though MA plans tend to fill in much of Medicare's cost sharing, as well as offer supplemental benefits at little to no additional premium, they usually have limited networks and attempt to manage care. It's these latter features that can make TM more attractive than MA to sicker beneficiaries.

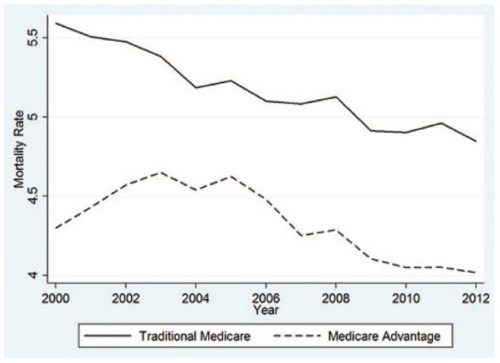

Reflecting the fact that they're sicker than MA enrollees, those in TM die at higher rates, as shown in the chart just below (the authors' Figure 1). The gap in mortality rate was larger before passage of the Medicare Modernization Act in 2003, which phased in a more complete risk adjustment scheme. However, the mortality rate difference persisted and remained fairly constant between 2006 and 2012. These findings hold up even after controlling for age, sex, race, and county fixed effect in a multivariate analysis.

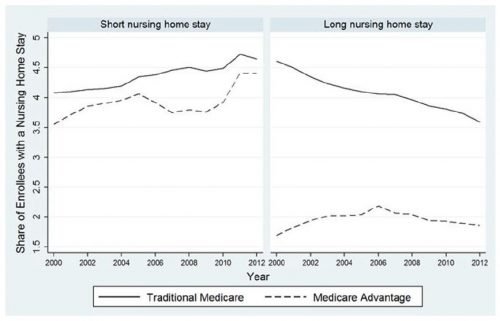

MA enrollees are also less likely to have a short (less than 90 days) or long (90 days or more) nursing home stay than are TM enrollees, as shown below (the authors' Figure 3). The long stay gap is much wider than the short stay one, and it closes somewhat in the post-MMA period. Nevertheless, this is further evidence of favorable selection into MA, though from these results alone — which, again, hold up in multivariate analysis — the possibility that MA plans manage care in a way that promotes greater efficiency and reduces nursing home stays cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor.

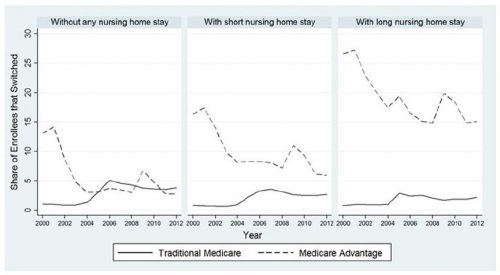

Finally, the authors provide evidence that sicker beneficiaries are more likely to leave MA than they are to enroll in it. The figure below (their Figure 5) shows that beneficiaries with a short or long nursing home stay are more likely to switch from MA to TM than vice versa.

These results are consistent with prior work, which I've written about before on this blog. For instance, analysis by Steven Martino and colleagues found that MA enrollees with depressive symptoms reported more difficulty getting needed care and drugs, and rated their experience with plans lower than those in traditional Medicare. As I wrote on The Upshot,

Older studies also found that sicker people tended to prefer traditional Medicare and were more likely to leave Medicare H.M.O.s. And other, more recent studies found that lower-income, less educated and sicker people reported worse experiences in Medicare Advantage than in traditional Medicare.

My takeaway from all this is that MA may promote efficiency and higher quality care, but it doesn't serve some types of sicker beneficiaries as well as TM. They vote with their feet and leave MA when TM appears relatively more attractive. Though not without cost, this degree of choice — that spans both private and public options — is a strength of Medicare and a large benefit to its beneficiaries, while remaining the focus of intense political attention.