In the U.S., Black and brown people are significantly more likely to become infected with COVID-19 and to die from it than white people. And, they are actually less likely to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Disentangling health care disparities like this is complex; there are many solutions to reduce disparities and improve health equity for everyone. Implementation scientists are well-positioned to address health care disparities such as this issue of inequitable distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Implementation science involves finding ways to increase the use of interventions that work and studying that process to do it better, faster, and in more places. Implementation frameworks, study designs, and methods are particularly useful to quantify and understand disparities, and to develop design strategies that increase the use of COVID-19 preventive and curative interventions for people of color. We can use implementation science to iteratively refine, systematically rollout, or stop interventions (if we find out the interventions are harmful).

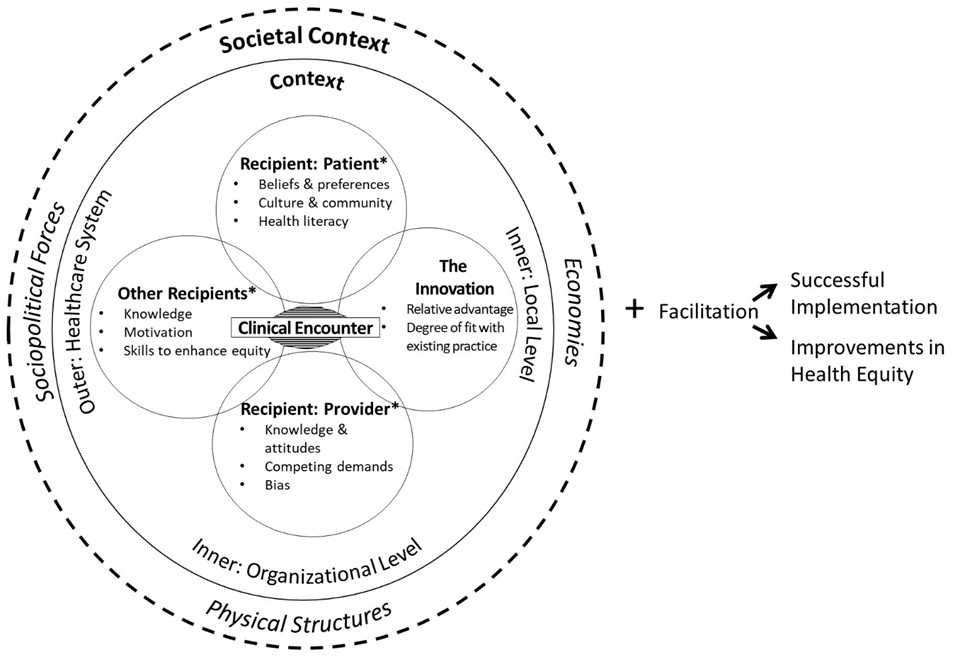

Frameworks help us explore root causes (determinants) so we do not miss or obscure potential drivers and can hypothesize strategies to mitigate those drivers. Frameworks are especially useful for people conducting implementation science to purposefully assess and document factors that predict health care disparities, like societal context, the encounters between patients and providers, and cultural factors of patients and providers. The Health Equity Implementation Framework is an existing implementation framework that our team adapted to include three health equity domains to focus purposefully on factors contributing to health care disparities, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Health Equity Implementation Framework

Let’s apply the Health Equity Implementation Framework to understand barriers and opportunities to reduce COVID-19 vaccine disparities by race and ethnicity. To do this, we’ll examine:

- The innovation being implemented

- Recipients and their cultural factors

- The clinical encounter

- Inner and outer context

- Societal context

The Innovation Being Implemented (COVID-19 vaccine)

These are characteristics of the intervention you want to implement. Although Black and brown people were underrepresented in trials for Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, placebo and vaccine groups had similar racial and ethnic makeups. Efficacy results suggested the vaccine worked similarly well across racial and ethnic groups.

Recipients (and their Cultural Factors)

Recipients of the innovation are those affected by changing how things are done in practice. In the case of the COVID-19 vaccine, recipients include more than just those receiving the vaccine, but also public health and health care staff, caregivers, or families. Cultural factors of recipients are formed by lived experience or norms of their community. Examples of cultural factors at play with the COVID-19 vaccine might include a health care providers’ practice of self-reflection and humility in approaching patients who are unsure about getting the vaccine. Implicit or explicit biases (e.g., racist beliefs) held by health care providers certainly affect the way an intervention is delivered (if at all). On the patient, caregiver, and family side, the ability to understand written and verbal health information as well as attitudes about the intervention also factor into implementation. All these examples, and more, can contribute to health care disparities.

Black people and people of color also have lived experiences of being oppressed by systemic racism in health care and research institutions, and thus have more to deliberate about whether they feel comfortable or safe getting the COVID-19 vaccine. And yet, some reports and polls indicate majority of Black and brown people want the vaccine or are open to wait and see how it evolves. This is an example of a societal context factor (see below) having downstream effects on recipients, such that Black and brown people have more to consider about a COVID-19 vaccine because of prior and recent mistreatment in health care systems.

Clinical Encounter

This is the interpersonal exchange between providers and patients. Factors related to the clinical encounter affect patient satisfaction, trust, and health outcomes, making it a critical moment in implementation efforts. This includes communication style (e.g., amount of speech), body language (e.g., no physical examination), affirmative care (e.g., gender-neutral language), and whether care is consistent with guidelines (e.g., standard screening for COVID-19 risk).

When Black and brown patients are interacting with health care staff and providers at routine appointments, are they being offered the vaccine at equitable rates to white patients? This remains to be seen, but other health care studies document a pattern of not screening or offering treatments to Black and brown patients as often as white patients.

Inner and Outer Context

These are settings and cultures within local clinics, hospitals, and health care systems that function as barriers or opportunities. Factors within the health care system, like availability of interpreters, hiring people of color as staff, workflows, or how health information technology is used, affect equitable care. One example with COVID-19 is when health care facilities do not collect data on patient race or ethnicity, it is impossible to measure and track any racial or ethnic disparity.

Societal Context

This consists of social determinants of health and more upstream factors including economies about how health care is obtained (e.g., insurance), physical structures where people live, work, and get treatment (e.g., accessible transit to vaccine sites), and sociopolitical forces including norms, movements, guidelines, laws, and policies (e.g., Black Lives Matter protests). These upstream factors, like policies about tobacco use, can exacerbate or minimize health care disparities. These factors feed on one another and create structures that exacerbate inequities and lead to worse health for people of color.

Societal context around the COVID-19 vaccine is illustrated by the CDC recommending that vaccine rollouts prioritize essential workers, emphasizing earlier access for Black and brown people in those roles. To add to the complexity, social norms about the vaccine conflict for some Black people with movements both encouraging and discouraging vaccination (as showcased in this Twitter thread describing a conversation between a Black doctor and Black restaurant worker). Regarding physical structures, are there enough distribution sites in predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods? Many sites require online appointments, which may be a barrier, while person-to-person contacts and mobile vaccine units show promise for communities of color.

Although this documentation is not comprehensive, you can see how planning a COVID-19 vaccination effort without considering issues unique to Black people and people of color would miss key barriers to overcome and strengths to harness.

Understanding barriers to addressing health care disparities is not enough, we must then map this thoughtfully to action. But, if we do not understand why a problem exists and what factors contribute to it, we risk putting effort toward the wrong targets and obscuring the real nature of oppression.