It's far too early to make anything like a complete judgement as to whether accountable care organizations (ACOs) will help address cost and quality issues in the U.S. health system. But it is about the right time to check the early returns. Based on them, I'd say ACOs are off to a promising start, but with no guarantee of long-term success.

It's important to recognize that the term "ACO" covers a wide variety of organizational types and contracting arrangements. Common threads include coverage and provision of care for a defined population (possibly retrospectively determined) with budgetary and quality goals to which bonus payments and/or penalties are tied. Also importantly, there are both public (Medicare and Medicaid) and private (commercial market) ACOs.

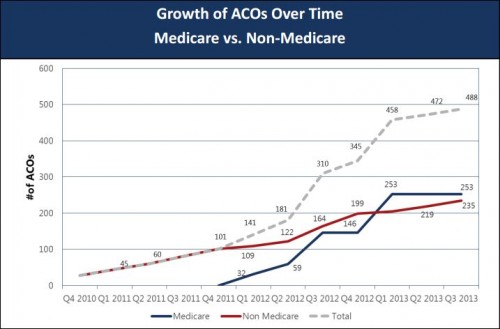

We tend to associate the ACO concept with Medicare, probably because Medicare reform provisions included in the Affordable Care Act promote the ACO model. However, non-Medicare ACOs predate Medicare ones and nearly half of all ACOs today are of non-Medicare types. See the chart below from Matthew Petersen, David Muhlestein, and Paul Gardner (PDF) of Leavitt Partners:

We don't yet now a great deal about Medicare ACO performance in general because the program is so new, though we do know a few things about where and why ACOs form. Nevertheless, early evidence is encouraging that ACOs can improve quality without increasing costs to Medicare.

We don't yet now a great deal about Medicare ACO performance in general because the program is so new, though we do know a few things about where and why ACOs form. Nevertheless, early evidence is encouraging that ACOs can improve quality without increasing costs to Medicare.

The 32 Pioneers generated a gross savings of $87.6 million in 2012. But only 13 of the Pioneers actually saved enough money to share those savings with Medicare, despite having invested in the programs and staff required to better coordinate care. And two Pioneers ended up owing the Medicare program $4 million. According to data released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services today, all 32 Pioneers succeeded improving quality and performed better than fee-for-service Medicare in 15 quality measures. For the 669,000 Medicare beneficiaries in the Pioneer ACOs, spending grew by only 0.3 percent, compared to 0.8 percent in conventional Medicare.In JAMA, John Toussaint and colleagues documented the impressive story of the best-performing Medicare ACO, though this is, by design, not the typical case. Private sector ACOs have experienced success as well. Analysis of the (non-Medicare) Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) of Massachusetts’ ACO-like Alternative Quality Contract (AQC) is also encouraging. The AQC began in 2009 with seven physician organizations in Massachusetts and had 15 participating groups by 2012. Investigators have found that the AQC was associated with spending reductions of 1.9% and 3.3% in its first and second years, respectively, along with evidence of improvements in quality. The news gets better. A recent study by Michael McWilliams, Bruce Landon, and Michael Chernew found that benefits of the AQC accrued to Medicare even though care for beneficiaries of the program was not directly subject to AQC terms. In other words, there was a spillover effect. Providers operating under the AQC reduced spending not just for BCBS, but also for Medicare.

The AQC was associated with significant reductions in spending for Medicare beneficiaries but not with consistently better quality of care. Similar to observed savings among BCBS commercial enrollees in the AQC, savings in Medicare grew in year 2 of AQC incentives, were greater for patients with more clinical conditions, derived largely from lower spending on outpatient care, and included reductions in spending on procedures, imaging, and tests. These findings suggest that global payment incentives in the AQC elicited responses from participating organizations that extended beyond targeted case management of BCBS enrollees. The AQC participants reported adopting several strategies that could have influenced patient care for which they did not bear financial risk, such as rewarding constituent physicians or groups for efficient practices, changing referral patterns, engaging in high-risk case management across multiple payers, and redesigning care processes to eliminate waste.For all that, there is still reason to be concerned about the future of ACOs. In a recent NEJM Perspective, Katherine Baicker and Helen Levy expressed the reservation shared by many health economists, myself among them: ACOs promote provider consolidation, and that consolidation can lead to higher health care prices and premiums. On a Leonard Davis Institute blog, Lawton Burns expressed other reservations about ACOs, and the AQC in particular. On Project Millennial, Ross White documented the implications of a misalignment between ACOs and their patients' incentives and what might be done about it. The open questions going forward are whether the benefits of ACOs outweigh their limitations and whether the model can be tweaked and reformed to address identified issues. Long-term, these are what we need to watch.