The Obama Administration is making a strong push to increase access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for addiction to opioids. In this and a prior post, I am reviewing evidence from previous MAT access expansion measures.

An estimated 2 million Americans abuse opioids, leading to $55.7 billion in social costs in 2007. In the 2000s, two laws aimed to make a dent in the problem by changing the accessibility of treatment for opioid dependence.

In 2000, the Drug Addiction Treatment Act (DATA) permitted qualified physicians to prescribe buprenorphine and related opioid substitution medications to up to 30 patients at one time and outside of opioid treatment programs like methadone clinics. The work of Andrew Dick and colleagues, which I described in a prior post, characterized the resulting expansion in access to substitution therapy.

In a subsequent paper published in Milbank Quarterly, the same authors (plus one more) assessed the association an Office of National Drug Control Policy Reauthorization Act of 2006 provision that permitted an increase in the number of patients to whom certain office-based physicians could prescribe buprenorphine at one time, from 30 to 100. The increase was available to physicians upon application, if they were actively treating patients with buprenorphine and had already been authorized for a year to prescribe it—so-called, "waivered" physicians because they held a waiver from the the registration requirements of the Controlled Substances Act.

Consequently, after 2006, two kinds of waivered physicians existed: "30" and "100," corresponding to the number of patients to whom they could prescribe buprenorphine under the law. Stein et al. studied how changes over time in numbers of 30- and 100-waivered physicians related to changes in grams of buprenorphine prescribed (both per capita), in urban and rural counties. They also examined the association of buprenorphine prescribing volume with numbers of methadone-dispensing opioid treatment programs and non-methadone dispensing substance abuse treatment facilities per capita.

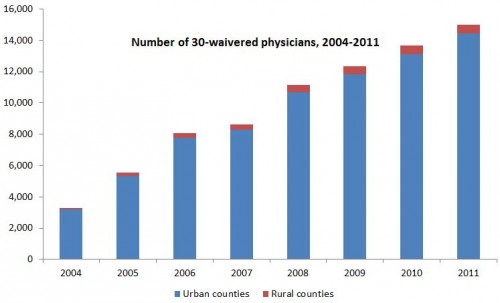

The two charts below, which I made from data in the authors' Table 1, show the growth in 30- and 100-waivered physicians over years 2004-2011 and by urban (blue) and rural (red) county status. The first chart shows substantial growth in 30-waivered physicians, from 3,293 in 2004 to 15,007 in 2011. 30-waivered physicians grew proportionally more in rural than urban counties over time, but from a much smaller base.

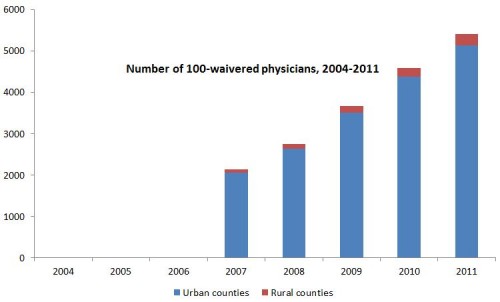

The chart just below shows that there were no 100-waivered physicians before 2007, as is expected since the law didn't allow it. In 2007, there were 2,132 100-waivered physicians, growing to 5,403 in 2011. Proportional growth in rural counties was much larger than in urban ones (about doubling in urban counties but growing almost four-fold in rural ones), but, again, urban counties started with a much higher base.

Not shown in my charts, but included in the authors' Table 1, the numbers of opioid treatment programs through which and substance abuse treatment facilities at which patients received buprenorphine grew over this period as well. Both started from a small base (71 of the former and 246 of the latter in 2004), and exceedingly small in rural counties (9 and 25, respectively). They experienced four-to-five-fold growth by 2011, across both county types.

Grams of buprenorphine dispensed was not consistently statistically significantly related to number of 30-waivered physicians, opioid treatment programs, or substance abuse treatment facilities. In the few years for which there was a statistically significant relationship for 30-waivered physicians, the results were small and negative, perhaps because relatively few 30-waivered physicians opt to dispense buprenorphine despite being authorized to do so.

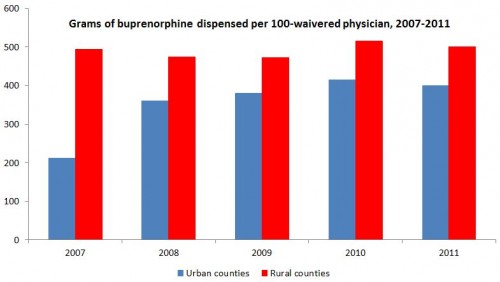

However, 100-waivered physicians had a large, statistically significant relationship with grams dispensed in urban and rural counties in all but one year (the 2007, rural result was not statistically significant), as shown in the chart below, which I made from data in the authors' Table 3. With the exception of 2007 and in urban counties, grams dispensed per 100-waivered physician was about 400 in urban counties and 500 in rural ones, in all years.

The authors put these numbers in clinical context:

Because the recommended daily dose of buprenorphine for treating opioid use disorders ranges is 16mg/day, with a maximum of 24mg/day (5.8 to 8.8 grams per year), our findings indicate that 24 (in 2007) to 45 (in 2011) additional patients received buprenorphine treatment per 100-patient waivered urban physician, assuming these physicians prescribe on the higher end of the daily dosage and individuals are treated for an entire year. For rural areas, assuming that waivered physicians prescribe on the higher end of the recommended daily dosage, our findings indicate that 57 additional patients received buprenorphine treatment per 100-waivered rural physician.

Scaling these figures up by the number of 100-waivered physicians in 2011, about 230,000 additional patients received treatment in urban areas and 15,000 in rural ones, assuming no substitution away from other means of treatment. The authors wrote,

Since buprenorphine’s approval, its availability from an increasing number of waivered physicians and substanceabuse treatment facilities [ref, ref] has raised the number of

individuals receiving buprenorphine [ref, ref] and often for the longer durations associated with improved outcomes. [...]

At the same time, more widely available buprenorphine can also have significant downsides, including medical emergencies due to ingestion by children [ref] diversion, and illicit use.

They found that,

The 2006 legislation allowing appropriately waivered physicians to treat more patients appears to have contributed to a substantial increase in the use of buprenorphine, which is encouraging at a time when a recent spike in heroin and illicit prescription opioid painkiller use has reinforced the importance of facilitating access to effective opioid agonist therapies.

As we combat the problematic use of opioids in America, it's worth keeping in mind that efforts to reduce use in the first place don't always help those already dependent. Policies that expand access to treatment are worthwhile complements.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs, an Associate Professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health, and a Visiting Associate Professor with the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.