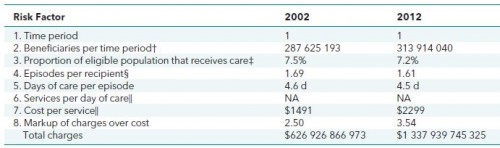

I wrote about Kevin Quinn's insightful typologies of health care payment methods in a prior post, which you should read before this one. In it, I discussed this table:

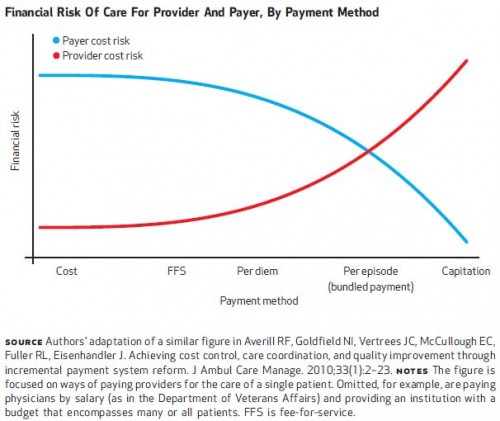

At each point (1-8) in this hierarchy of risk, AmeriCare bears risks in changes in units at and above that point and USHC bears the risk for changes in units below that point. That's because it's a nesting of units: beneficiaries within time period, recipients are a subset of beneficiaries, each recipient has one or more episodes, each of which can span on or more days, etc. Another way to see this is in the figure Rick Mayes and I included in our 2012 Health Affairs paper:

Because of the nesting of risk, if you multiply the numbers down the columns in Quinn's table above, you get the bottom line total cost: 1 × 313 914 040 × 7.2% × 1.61 × 4.5 × $2299 × 3.54 = $1 337 939 745 325, or $1.3 trillion, which is total 2012 spending on inpatient hospitalization.

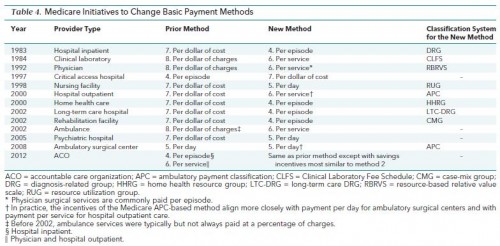

Over the decades, Medicare has changed the unit on which it pays various providers many times. The following table from Quinn's paper documents those changes. Except for the payment method change for critical access hospitals in 1997, all changes have been to move up the hierarchy, which shifts more risk to providers and away from Medicare. The shifting of risk to providers reflects the idea that, given the right incentives, it is they, not Medicare that more accurately can assess how to provide the right care to the right patient at the right time.

In most transactions in most markets, the units are the thing that is being bought and sold. Health care is only different to the extent participants in transactions are motivated by non-pecuniary factors. Quinn writes that the fact that payment for health care services can be and has been rendered at different units reflects the notion that "the 'product' being purchased and delivered [] remains variable and unsettled." It's a deep insight baked from some rather dry ingredients.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs, an Associate Professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health, and a Visiting Associate Professor with the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Boston University, or Harvard University.

Editor's Note: AcademyHealth's National Health Policy Conference (February 1-2 in Washington, DC) features several sessions on payment reform, innovations, and alternate models. Explore the agenda here.