A fascinating, new article on reference pricing by James Robinson and Timothy Brown appeared in the August issue of Health Affairs. The results are interesting enough, and I'll get to them, but the well-articulated market context and potential implications of reference pricing are what caught my eye. (If you're new to the concept of reference pricing, my earlier post on this blog will serve as a primer.)

The employer focus on benefit design and consumer cost sharing [including reference pricing] contrasts with the focus on provider contracting in traditional price negotiations, as these strategies have been countered by consolidation and market power on the part of providers. Once hospitals in a local market have merged, they can refuse to contract with a health insurer except as a group and thus can successfully demand higher prices for their services.Already, this is an interesting frame, suggesting that traditional selective contracting has become less viable due to provider consolidation. Yet the desire for control on spending on the part of employers and consumers remains. Instead of buckling under and paying consolidated providers their demanded prices, reference pricing sends a signal that the plan's price is firm, though the consumer may pay more if s/he desires.

Payments to hospitals for services subject to reference pricing above the employer’s contribution are not limited. The consumer therefore is potentially exposed to very high cost sharing if he or she does not select a provider whose charge will be covered by the employer. The employer sets the contribution level high enough to cover the prices charged by a sufficient number of hospitals in each geographic region. The employer decides how many hospitals in each region it wishes to include, balancing the employees’ preferences for larger numbers of hospitals and the price reductions it can expect if it uses smaller numbers.There is, of course, a danger that the employer will not set the contribution level high enough so that a "sufficient number of hospitals in each geographic region" are willing to offer services at that level. Consumer exposure to high prices could be a problem. It's a balancing act. Where things get interesting is in considering market responses.

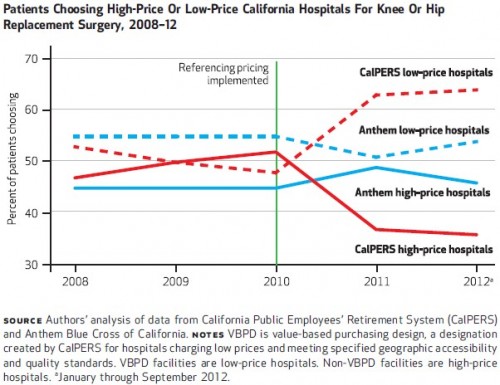

Facilities whose prices fall below the employer’s maximum payment may respond by increasing their prices. This would not make them less appealing to consumers, because employers typically do not share with employees the savings from selecting hospitals whose prices fall below the limit. [Though, they could!] However, facilities may reduce their prices if they believe that the employer is likely to reduce its payment contribution further in future years or share savings with employees who choose low-price hospitals. [See?!] Hospitals whose prices exceed the employer’s maximum payment may reduce their prices in order to be designated a high-value facility and retain patient volume. Alternatively, high-price facilities may not change their prices on the assumptions that price reductions would not be offset by volume gains and that some patients would continue to use their services and pay the extra cost sharing. Hospitals’ pricing responses may depend on whether the employers using reference pricing serve as bellwethers for other employers.Obviously, this warrants investigation. What actually happens in specific markets? The authors consider the January 2011 change by California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) to reference pricing for knee and hip replacement surgery, contrasting the experience with that of Anthem Blue Cross of California, the largest insurer in the state, which did not implement a reference pricing scheme at that time. Descriptively, the chart below illustrates what happened. Before implementation of reference pricing by CalPERS, roughly an equal share of patients chose low- and high-price hospitals for knee or hip replacement surgery, though the shares varied by year. Among Anthem patients, 55% chose low-price hospitals and 45% chose high-price ones. After CalPERS switched to reference pricing, shares of Anthem patients by hospital price stayed relatively constant (some fluctuation by year, but returning close to pre-CalPERS switch levels by the end of the study period). However, CalPERS patients responded strongly to the reference pricing incentives. Almost 65% chose low-price hospitals and 35% high price hospitals by 2012. Qualitatively, these findings were corroborated in a more rigorous multivariate analysis.

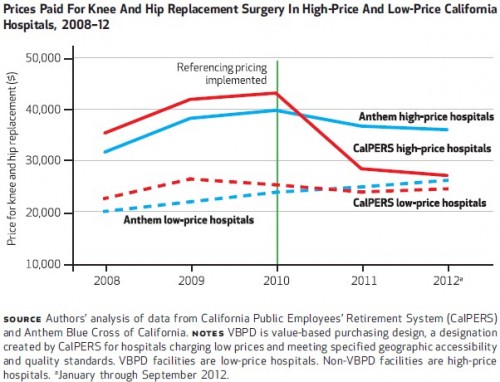

An important question is, how did hospitals respond to these shifts in patient volume. The chart below tells the story on price. CalPERS high-price hospitals dramatically lowered their prices, while prices for CalPERS low-price hospitals and Anthem high- and low-price hospitals held steady or changed relatively modestly.

An important question is, how did hospitals respond to these shifts in patient volume. The chart below tells the story on price. CalPERS high-price hospitals dramatically lowered their prices, while prices for CalPERS low-price hospitals and Anthem high- and low-price hospitals held steady or changed relatively modestly.

Our final estimate, using multivariate statistical methods to take into account changes in the demographic and severity mix of patients, is that reference pricing was responsible for a 20.2 percent ($7,028 per case) decrease in hospital prices on average in 2011. These changes were sustained in the second year after implementation and were significant. The total savings in 2011 attributable to reference pricing were $3.1 million ($7,028 per patient multiplied by 447 patients). Of this amount, $2.8 million accrued to CalPERS from lower payments to hospitals, and $0.3 million accrued to CalPERS enrollees from lower out-of- pocket cost sharing.Of course, this is one study and the extent to which results generalize to other conditions and other systems is unclear. Moreover, the impact of reference pricing on access and quality of care is not addressed in this work. Be that as it may, if the authors are right that reference pricing is an alternative to traditional selective contracting, which itself is becoming less feasible due to provider consolidation, then researchers may get many other opportunities to investigate these issues. --Austin Frakt