Last month on this blog, I surveyed the literature on consumers’ responses to high numbers of health plan choices. The thumbnail sketch is that, when asked to choose among too many plans, consumers have difficulty selecting the best plan. However, the resulting mixing of consumers across plans plays a risk-spreading role. Some relatively healthier consumers who would be better off in skimpier, cheaper plans select more generous, expensive ones, improving the risk selection those plans experience. This post is an extension and update. In Medical Care Research and Review, Mark Schlesinger and colleagues consider a related issue pertaining to selection of a primary care physician. They consider not just the number of options consumers might choose from, but also the amount of information on physician quality available to inform their choices.

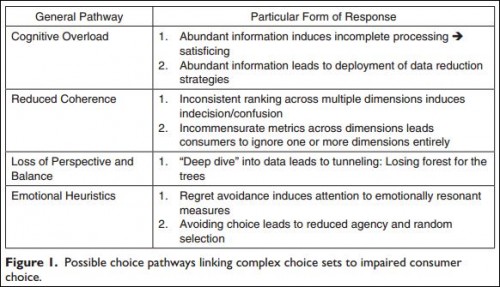

When consumers have more doctors to choose among or more types of information available on their comparative performance, they are less likely to pick the doctors who objectively perform best (as measured by standardized performance metrics) and more likely to choose doctors whose care is inferior to other available clinicians. [...] [W]hen people must choose among a large number of options in a complex choice task, they adopt heuristic strategies to reduce the amount of information they must consider—strategies that are “boundedly rational” but can result in a suboptimal decision []. Even for decisions that have high stakes, such as those involved in medical care, many consumers will make choices in ways that reflect bounded rationality.The authors go on to point out that it isn't just the number of options that makes choice complex, it's also the amount of information characterizing those options. The more information, the harder is the evaluation problem. Their Figure 1, below, describes four ways consumers can go wrong.

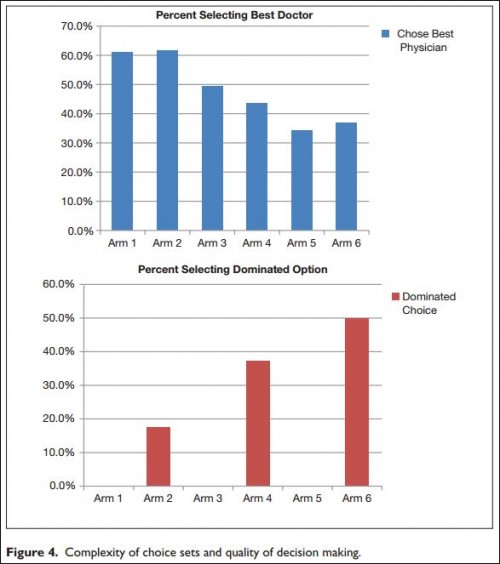

In a controlled experiment with about 800 subjects, the investigators found that, indeed, more information impaired optimal decision making. In the figure below, the numbered arms of the experiment index different levels of informational complexity, as well as number of choices. Without going into too much detail, in general, the higher number the arm, the more complex the decision space, either in number of choices or amount of information available per choice, or both.

In a controlled experiment with about 800 subjects, the investigators found that, indeed, more information impaired optimal decision making. In the figure below, the numbered arms of the experiment index different levels of informational complexity, as well as number of choices. Without going into too much detail, in general, the higher number the arm, the more complex the decision space, either in number of choices or amount of information available per choice, or both.

The top panel of the figure illustrates that as choice sets become more complex, fewer subjects chose the best physician. The bottom panel pertains to cases for which there is a dominated choice, i.e., one that is suboptimal in every dimension (every quality measure). This was only true for arms 2, 4, and 6. Choosing a dominated option is always wrong. Yet, as more information and choices are available, more people do so.

It is not surprising that too much information can overwhelm consumers' ability to make rational choices. Yet, that fact is often overlooked in analysis of consumer behavior, and it it makes a huge difference. In a recent NBER working paper, Benjamin Handel and Jonathan Kolstad illustrate just how huge. They consider the effects on health insurance choices of humans' lack of information (or lack of ability to apprehend information) about plan attributes and the time and hassle costs they experience from and expect of plan use. These are called "frictions."

By their estimate, if one doesn't account for such frictions, one comes to the erroneous conclusion that people choose more generous plans in large part because of risk aversion, i.e., the desire to protect oneself from loss. However, if one accounts for such frictions, most of that risk aversion explanation goes away. My plain language summary of their work is that

The top panel of the figure illustrates that as choice sets become more complex, fewer subjects chose the best physician. The bottom panel pertains to cases for which there is a dominated choice, i.e., one that is suboptimal in every dimension (every quality measure). This was only true for arms 2, 4, and 6. Choosing a dominated option is always wrong. Yet, as more information and choices are available, more people do so.

It is not surprising that too much information can overwhelm consumers' ability to make rational choices. Yet, that fact is often overlooked in analysis of consumer behavior, and it it makes a huge difference. In a recent NBER working paper, Benjamin Handel and Jonathan Kolstad illustrate just how huge. They consider the effects on health insurance choices of humans' lack of information (or lack of ability to apprehend information) about plan attributes and the time and hassle costs they experience from and expect of plan use. These are called "frictions."

By their estimate, if one doesn't account for such frictions, one comes to the erroneous conclusion that people choose more generous plans in large part because of risk aversion, i.e., the desire to protect oneself from loss. However, if one accounts for such frictions, most of that risk aversion explanation goes away. My plain language summary of their work is that

[c]ontrolling for frictions is huge, leading to the conclusion that consumers (at least those in the sample studied) are far less risk averse than implied by a model that does not do so. Put another way, humans may not be choosing the plans they do for risk protection purposes. They may, instead, be making mistakes that homo economicus would not. I'm not even sure it's fair to call them "mistakes." Let's just say, "we're human."--Austin