Adequate access to primary care is necessary to achieve many of the population health improvement goals of the Affordable Care Act. However, the ACA's expansion of health insurance is somewhat at odds with increasing that access: lower out-of-pocket costs will facilitate access to care, but dramatic expansion of coverage could also stress the supply of primary care providers, limiting access. To assess how the ACA affects access to primary care, we need baseline (pre-expansion) measures of it.

In a new study published in JAMA Internal Medicine (JAMA IM), Karin Rhodes and colleagues provide the latest estimates of that baseline.* It's a well-crafted study, documenting access challenges facing Medicaid beneficiaries in particular. I will warn you up front, however, it's only a partial view of access issues. An analysis published separately by many of the same investigators provides a different and seemingly contrasting view. I will comment on that separate analysis in a subsequent post later this week.

With a phone call, audit-based (i.e., simulated patients) approach, Rhodes and colleagues examined pre-ACA primary care access by insurance status—Medicaid, private coverage, and uninsured—over the period November 13, 2012 to April 4, 2013 and in ten states: Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Massachusetts, Montana, New Jersey, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Texas. These states account for between one-quarter and one-third of each of the nonelderly population, Medicaid enrollees, and the uninsured.

Simulated patients called ("audited") primary care offices seeking new visits. Nearly 11,400 appointments were attempted across the ten states, about 5,400 by a private plan enrollee, about 4,400 Medicaid, and about 1,600 uninsured (all simulated and with a standardized protocol, of course).

To be in the sample for Medicaid, the office had to have a contract with a Medicaid plan, whether primary care case management or a Medicaid managed care plan. If asked, Medicaid callers identified their insurance status as that of the specific plan accepted by the office called. Private plan callers identified themselves as covered by the private plan with the highest market share in the office's county, again if asked. If the office did not accept that plan, a second call was made during which the caller identified him/herself with the plan with second highest market share if asked. Offices that did not accept either of the top two plans were removed from the private plan sample.

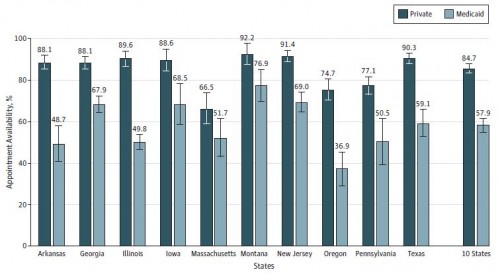

The chart below, from the paper, shows the new patient appointment rates by state for Medicaid and private insurance and averaged over all ten states. On average, private plan callers were offered an appointment 85% of the time and Medicaid callers only 58% of the time. This suggests significantly higher primary care access barriers for Medicaid patients relative to privately insured ones.

Appointment Availability for Private and Medicaid Callers

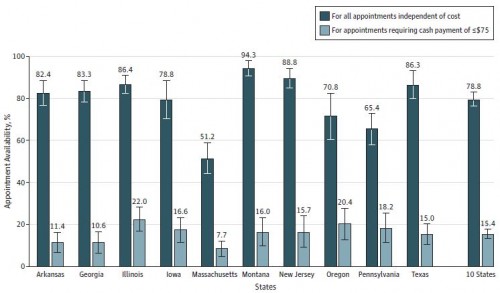

A common knock on Medicaid is that it's worse than being uninsured (it isn't), and the above results would seem to support that claim. But, in fact, this assertion is difficult to test in a study like this one. One can't fairly compare Medicaid and uninsured populations without controlling for income, which can't be done in an audit study for which the unit of analysis is the office, not the patient. What the investigators did, however, was examine the rate at which uninsured callers could obtain appointments at full and reduced cost, where "reduced" meant $75 or less at the time of visit. The thinking here is that appointments requiring more than $75 at time of visit would be financially difficult for uninsured patients with Medicaid-like incomes. (The $75 was selected because it was half the median cost; a weakness of this approach is that this cut-off is not grounded in any particular affordability standard.)

The chart below, also from the paper, shows the results. On average uninsured callers were 79% successful at obtaining an appointment, much better than Medciaid. But, only about 15% of uninsured callers were offered an appointment that would cost $75 or less at the time of visit, which is much worse than Medicaid and an arguably fairer comparison to it.

Appointment Availability for Uninsured Callers

The investigators also found that median wait times were between 5-8 days for private and Medicaid callers alike except in Massachusetts where they were 13 days for private and 15 days for Medicaid callers. This, perhaps, indicates that coverage expansion to the extent experienced in Massachusetts could substantially increase waiting times, though it is unclear whether this degree of increase is clinically significant. It’s worth noting, however, that new patients without an established provider are more of a rarity in Massachusetts—one of the states with the highest percentage of adults saying they have a usual source of care (see Exhibit 11, here). The experiences of patients who already have established care are likely to be different.

Some conclusions: The study results suggest that the primary care system has the capacity to take on new, privately insured patients. They seem to suggest that Medicaid enrollees may face greater access problems than privately insured patients, though not as severe as (arguably) comparable uninsured patients. What they really show is that Medicaid patients (and comparable uninsured patients) will need to make better targeted or more calls to get appointments. According to the results above, to achieve the same rate of success at securing an appointment, Medicaid patients who were calling offices at random would, on average, have to call about two offices for every one a privately insured patient would. (See also the invited commentary about this work by Andrew Bindman and Janet Coffman.)

But, we should ask, do Medicaid patients call offices randomly? Is the additional effort they may have to exert to obtain appointments an unreasonable burden? Does it affect outcomes? My next post on related work will shed some light on these questions.

* Several other papers relevant to access to care by Medicaid patients and Medicaid expansion were also published in JAMA IM today: Chima Ndumele and colleagues found that adult Medicaid enrollees in ten states that expanded Medicaid between 2000-2009 experienced no loss in access to care or increased emergency department use, relative to 14 neighboring control states that did not initiate expansions. This paper, among others, is summarized in an editorial by Mitchell Katz. Finally, using National Health Interview Survey data from 2010-2012, Sandra Decker and colleagues found that low-income adults in states not expanding Medicaid in 2014 were in worse health and had poorer access to care, relative to expansion states. I.e., they had more to gain from coverage expansion than states that are expanding Medicaid.

--Austin