I've written about obesity so many times that there are times I find myself in despair. Things seem not to work as well as we'd like. Intervention after intervention seems to fail. Keeping weight off seems as hard as losing it in the first place. And yet we are inundated over and over that obesity and its health implications are a present and future driver of increased health care costs.

A recent review in the journal Cancer looked at "Obesity and economic interventions". It's absolutely worth your time.

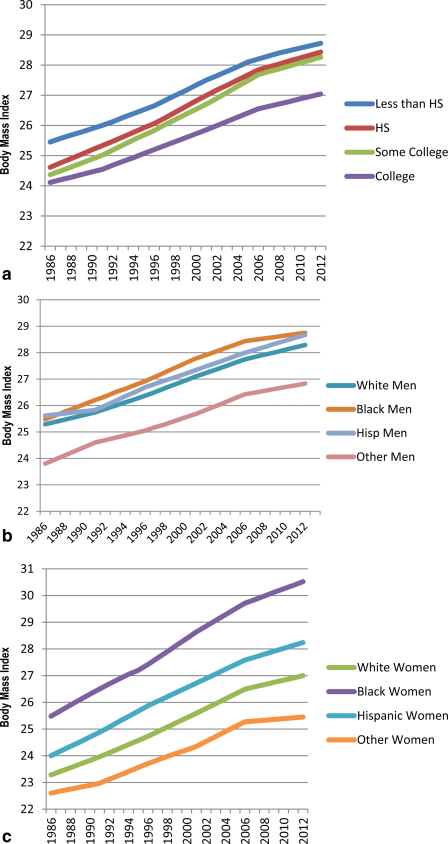

The first thing that hit home was how much of a holistic problem obesity has become. In the following charts, the researchers plotted the body mass index of various groups over time, from 1986 through 2012:

The top chart shows the BMI of people in the US, broken out by education levels. Many studies like to show that there are disparities in obesity, and there are. People with less education are more likely to be obese than people with more education. But it's striking how all groups have gotten worse over time. They're all getting obese, at remarkably similar rates.

The bottom two charts show the same thing, but for race/ethnicity, and for sex. Men of all races and ethnicities got obese at similar rates, and there's not much difference between White, Black, and Hispanic men. But women see real differences between White, Black, and Hispanic races and ethnicities. Again, though, these differences held steady over time. All of them increased their levels of obesity.

These data paint a compelling picture for how we need a holistic approach to the obesity problem. It's not about one sex, or one race, or one ethnicity, or one socioeconomic status. It's everyone. And, when there's a problem that affects everyone, it may be time for a policy prescription, not a medical one.

The paper cites a number of factors that have likely contributed to this problem. We in the United States have the cheapest food in all of history when measured as a proportion of disposable income. Our food also comes with more calories than ever before for the price.

Further, the paper offers a number of potential actions we can take. They discuss the uses of taxes and subsidies to nudge American's habits in ways to improve nutritional intake. These can be applied on both the production and consumption sides. These approaches all come with positive and negative aspects, and many have succeeded and failed in the past. They present three recommendations based on empirical evidence and expert opinion:

1) incorporate health impact assessments to review agricultural polices so that they do not have a deleterious impact on population rates of obesity2) implement a tax on SSB (sugar sweetened-beverages)

3) examine how to implement fruit and vegetable subsidies targeted at children and low-income households.

Overall, the manuscript is balanced and thoroughly referenced. I can't recommend it enough. Go read it.