I thought the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) strictly applied a cost-effectiveness threshold to make its care coverage recommendations for the country's National Health Service (NHS). Helen Dakin and colleagues explain that the body is actually much more flexible. Nevertheless, it's hard to fathom anything like it in the United States.

According to the most recent NICE methodology document, the decision to recommend a health technology that has an incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) below £20,000 is normally based on cost-effectiveness. Above that threshold, other criteria are more likely come into play including uncertainty, innovation, non-health outcomes, end-of-life considerations, and stakeholder perspectives on quality of life gains. Technologies aimed at children, disadvantage populations, and severe diseases are also given special consideration.

Thus, it is not the case that every technology with an ICER below £20,000 (or any particular threshold) is covered in the U.K. and that every technology above it is not. Instead, NICE makes each recommendation based on a deliberative, committee process that exercises judgement across a range of criteria rather than applies pre-set rules.

To gain a more nuanced understanding of how NICE tends to apply cost-effectiveness and other criteria, Dakin and colleagues analyzed all 190 technology assessments that were completed by the organization through 2011 and that were informed, at least in part, by cost-effectiveness. (A smaller number of decisions are made without any cost-effectiveness data. These were not analyzed.) Their approach builds on prior work: Devlin and Parkin (2004) "found that cost-effectiveness was the key driver of NICE decisions, although uncertainty and burden of disease were also significant." Dakin et al. (2006) "found that decisions were influenced by cost-effectiveness, clinical evidence, technology type, and patient group submissions." Cerri et al. (2014) "found that in addition to cost-effectiveness, demonstration of statistical superiority of the primary endpoint in clinical trials, the number of pharmaceuticals appraised within the same appraisal and the appraisal year were also important." (All quotes from Dakin et al.)

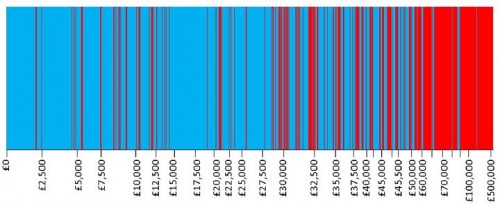

Not surprisingly, Dakin and colleagues found that the proportion of technologies recommended for approval by NICE decreases with increasing ICER. This is conveyed in their Figure 2, reproduced below (click to enlarge). Decisions are arrayed by ICER, indicated on the horizontal axis (not in a uniform scale). Recommended technologies are colored in blue and rejected ones in red.

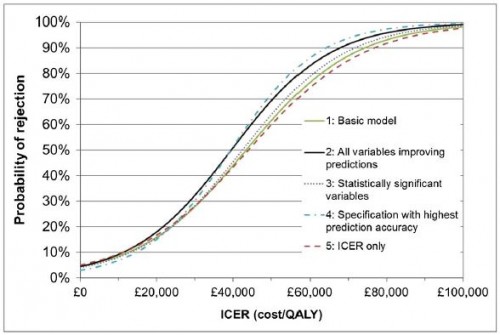

We estimate that, in practice, the ICER at which the probability switches from more-likely-to accept to more-likely-to-reject is between £39 000 and £44 000: well above the [] £20 000–£30 000 range [typically suggested as a threshold].

This is shown in the authors' Figure 3, shown below.

[Apart from ICER], no other factors besides the type of condition had a significant effect on NICE decisions, although allowing for clinical evidence, alternative treatments, paediatric population, patient group involvement, publication date, type of process[...], orphan status, innovation and uncertainty improved prediction accuracy.

It should be noted that, although the other factors besides ICER did not play a statistically significant role in this analysis of NICE decisions, for any particular decision they could be decisive. The first figure in this post (the authors' Figure 2) suggests just that.

Though NICE does not strictly apply a cost-effectiveness threshold in its decision-making process, cost-effectiveness is clearly a predominant consideration. That's much less common in the United States (though not completely foreign), and certainly not a factor in Medicare coverage decisions. Though some economists would be happy to see cost-effectiveness more routinely considered by insurers and consumers in the U.S., David Cutler, for one, does not think it's necessary at this time.

[T]he most important rule of health care management is this: never put care providers in a position of denying care for financial reasons.

Instead, Cutler recommends we focus on reducing purely wasteful (zero value care) first. Typically, such care arises from the application to an overly broad population of therapies that are valuable to only a subset. A classic case is the prescribing of antibiotics (which are of high value, when used appropriately) to patients with viral infections. There are many others.

As a normative matter, whether Cutler's view is right is debatable. Nevertheless, I believe he is right to imply that cost-effectiveness is not going to be a pervasive coverage consideration in the United States for some time. Even statutorily established health care evaluative bodies that are circumscribed in doing so, like the Independent Payment Advisory Board or the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, are controversial. Notwithstanding the "wiggle room" NICE has in applying criteria other than cost-effectiveness, something like it for U.S. Medicare (and more) is hard to fathom.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.

[Editors note: AcademyHealth also recently released an report on international perspectives on comparative effectiveness analysis and quality improvement. That report can be found here.]