Two recent studies of Medicare Advantage (MA) assess its cost and value. In Health Affairs, Brian Biles, Giselle Casillas, and Stuart Guterman largely examine its costs. In an NBER working paper, Vilsa Curto and colleagues also consider its value, among other things.

A complexity of MA is that it's not just one thing: costs and value vary by location and type of plan. Rural counties, where competition among providers is lower, tend to harbor plans with the highest MA costs, according to insurers' bids to Medicare for provision of the basic Medicare benefit for an average risk beneficiary. Plans in some counties report costs as high as 26 percent above traditional Medicare. However, in others, it can be as low as 28 percent below. Note that what varies is not just plan costs, but those of traditional Medicare too.

There are three principle MA plan types: HMOs, PPOs, and private fee for service (PFFS) plans. It's HMOs that are lowest in cost, because they tend to offer the most restrictive networks. As Biles et al. report, based on 2012 data, HMOs have costs 7 percent below traditional Medicare on average. But PPOs' and PFFS plans' costs are 12-18 above those of traditional Medicare. PPO networks are less restrictive than HMOs', and PFFS plans do not establish networks at all.

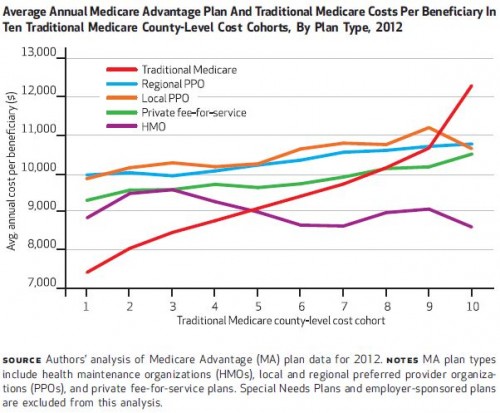

The chart below reports the costs of traditional Medicare, PPOs (both those that contract on a county-by-county basis — local PPOs — and those that do so in multi-state regions), PFFS, and HMOs. It does so for 10 groups of counties of roughly equal numbers of beneficiaries, stratified by their traditional Medicare costs. The lowest cost cohort has annual traditional Medicare costs per beneficiary of about $7,400. The highest is closer to $12,000. (The national average is $9,400.)

Except in the very highest cost counties, PPOs' and PFFS plans' costs are above those of traditional Medicare. But HMOs' costs are at or below traditional Medicare costs in most county cohorts. Putting other considerations and caveats aside for the moment, on costs alone, in general it's not clear whether one should prefer traditional Medicare or HMOs. (Perhaps tipping the scale, HMOs may also contribute to lower costs in traditional Medicare as well.)

Using data from a bit earlier (2006-2011), Vilsa Curto and colleagues also find that, on average, MA plans cost less than traditional Medicare by about 7 percent. They also consider the benefits that MA delivers to enrollees: $76 per month in actuarial insurance benefits (like lower copayments and coverage of services beyond the basic Medicare benefit). But, this is offset by the effects of more narrow networks offered by HMOs. Factoring that in, the net benefit to enrollees is about $49 per month.

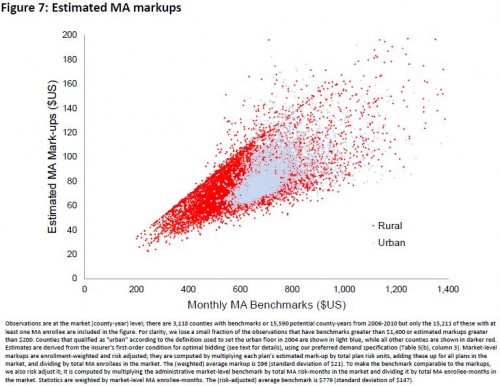

Importantly, taxpayers capture none of the savings HMOs offer, because of high program payments to plans, about $94 per month above the cost of traditional Medicare. This is also the amount captured by insurers in profits, according to the authors. "On a percentage basis, this suggests that plan margins are on the order of 16%," they wrote. The chart below illustrates monthly, per enrollee profits (or markups), plotted against Medicare's maximum allowable, monthly, per-enrollee subsidy to plans (benchmarks), which vary by county.

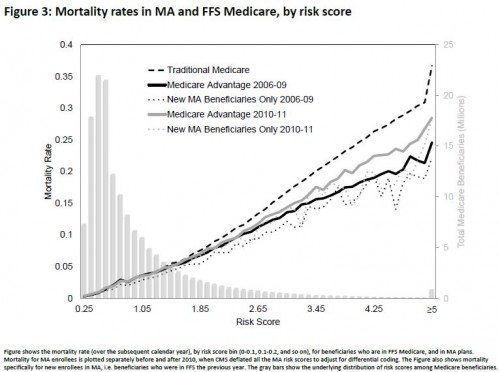

Curto et al. acknowledge that risk adjustment does not fully account for the differences in MA vs. traditional Medicare populations. Using population mortality, their estimates also control for health differences that may not be captured by risk adjustment, which is summarized by a risk score (1 is average and lower is healthier, higher is sicker). As shown in the figure below, mortality rates in MA are below those of traditional Medicare, suggesting the former serves healthier beneficiaries. (The authors discount the possibility that MA keeps people healthier and living longer because there is no evidence mortality rates fell in counties where MA enrollment grew rapidly.)

Finally, we should acknowledge the observed upcoding of MA beneficiaries: they can appear to be sicker than they would were they in traditional Medicare just because of medical coding differences. This phenomenon could cause risk adjustment to over-correct, making MA appear less costly than it really is.

All in all, the findings of Biles et al. and Curto et al. are consistent with prior work. For some plan types (HMOs in particular) and in some areas (less rural ones in particular), MA can probably deliver the basic Medicare benefit more efficiently than traditional Medicare. But MA plans are paid well above traditional Medicare costs, allowing insurers to pocket some extra profit, though also providing them resources to offer richer benefits. Taxpayers are footing the bill.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.