My colleagues and I like to tell ourselves, if not others, that our research makes an impact by informing policymakers. That's something that should be measured. For comparative effectiveness research (CER) specifically, Joel Weissman and colleagues recently did so.

In a study published in the Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, Weissman et al. surveyed Medicaid program medical and pharmacy directors in all states. Their overarching question: How do senior coverage policymakers view and use CER? (The sense of policymaking here is about what medical treatments to cover through a Medicaid program, and in what ways.)

One thing they learned is that Medicaid policymakers love RCTs, consensus statements or guidelines from national professional societies, and systematic reviews. About 90% of them said they used evidence in these forms. About 75% said they used expert opinion, and about 60% used observational studies with external (not the plan's) own data. Less than half (45%) used observational studies based on the plan's data.

It's a bit difficult to interpret these statistics, however, since consensus statements, guidelines, and expert opinion are themselves often based on studies, whether experimental or observational. What these results may be telling us is how influential the final packaging may be. The best way to get an observational study to be used by a Medicaid program, for example, may be to try to get it worked into a consensus statement, guideline, or systematic review.

That advice looks even better if we consider how useful these policymakers found each type of evidence (or evidence delivery method). The authors found that observational studies are a lot less likely to be perceived as "very useful" than other some other evidence sources.

The percentage who said each type of evidence or information was ‘very useful’ in setting policy was highest for RCTs (73%), followed by 68% for guidelines, 53% for systematic reviews, 42% for expert opinion, 20–21% for observational studies and 8% for patient experience/advocacy.

(There was a lot less variation when weakening the criterion to "at least 'somewhat useful'".)

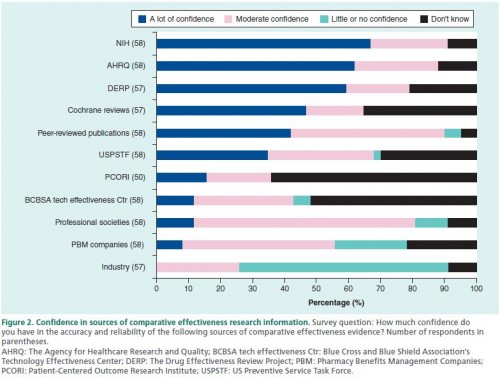

The authors also asked about confidence in different research sponsors and sources. The results are in the chart below. Keep in mind that a study could fall into more than one category (e.g., a peer-reviewed publication that is sponsored by NIH). It looks like PCORI and the USPSTF have some work to do in boosting confidence to Medicaid policymakers.

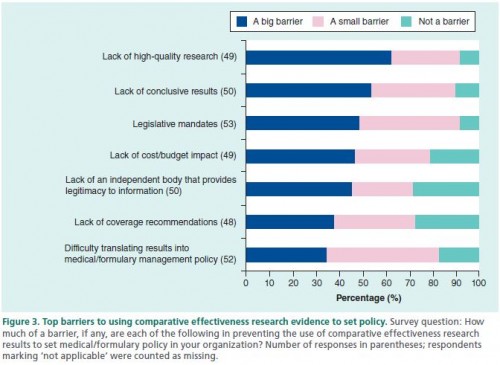

Respondents reported various barriers to using CER. The top ones point to the need for more research and more cost/budget analysis.

That about 45% reporting "the lack of an independent body that provides legitimacy to information" is troubling, particularly because that's what I perceive many of the organizations in the previous chart above as doing (e.g., USPSTF, The Cochrane Collaboration). The authors offer other organizations to consider:

In Washington state, the Health Technology Assessment Program was created by statute in 2006 to consider safety, clinical effectiveness, and cost–effectiveness in making coverage decisions for the state's Medicaid, workers’ compensation program and the public employee self-funded plan [7]. More recently, the New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council was formed to provide independent guidance on how information from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reviews supplemented with budget impact and cost–effectiveness information can best be used by public and private payers, clinicians and patients [8]. The Washington state program has legal authority to set policy, while the New England Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council does not make specific coverage recommendations but serves as an independent, objective source of interpretation and guidance. Medicaid policy makers in other states may be interested in having external validation of their own conclusions or additional sources of trusted information they can apply to their policy making.

Between the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the National Institute of Health, the Veterans Health Administration, and other organizations and agencies, billions of dollars have been spent on comparative effectiveness research (CER), with more to come. That's the input. The study by Joel Weissman and colleagues tells us a little bit about the output and how it's perceived and used.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.