Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage (MA) are probably at least a little healthier than those who enroll in traditional Medicare (TM, also known as fee-for-service or FFS Medicare). But, according to a recent paper by Michael Geruso and Timothy Layton, MA enrollees appear much sicker than they would if enrolled in FFS Medicare, due to how their illnesses are coded. Because plans are paid more for apparently sicker enrollees, this "upcoding" costs taxpayers a lot of money.

Plan payments for an enrollee are proportional to her "risk score," which is based on demographics and diagnoses. An enrollee of average risk has a risk score of 1.0. Lower risk scores correspond to lower expected spending. Higher risk scores correspond to higher expected spending.

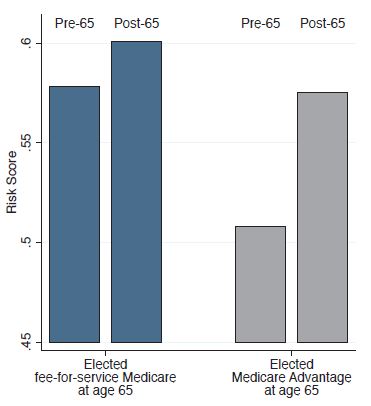

The following figure, from the authors' analysis of 2011-2012 Massachusetts' All-Payer Claims Dataset (APCD) tells you all you really need to know. (For this figure, fee-for-service Medicare enrollees were those with Medigap claims in the APCD.)

The figure shows that risk scores tend to increase as people transition to Medicare at age 65, whether to fee-for-service or Medicare Advantage. But, (a) MA enrollees are healthier than FFS enrollees and (b) MA enrollees' risk scores increase much more than FFS enrollees. This is the signature of upcoding. These findings are upheld in the paper in several other analyses and with other sources of data.

For example, the authors' primary analysis exploits variation in MA market penetration (the proportion of beneficiaries enrolled in the program) over time (2006-2011) and across markets. Markets in which MA penetration is higher tend to have higher average risk scores, precisely what you'd expect from upcoding. This analysis reveals that MA risk scores are 7% higher than FFS risk scores. This difference is equivalent to 7% more beneficiaries becoming paraplegic, 12% more developing Parkinson’s disease, or 43% more becoming diabetics. These findings are consistent with those of Kronick and Welch, about which I wrote previously. They are also consistent with media reports and legal allegations.

Another analysis was based on the dataset colleagues and I used to assess premiums and quality for MA plans vertically integrated with providers. The authors found that these organizations had much higher risk scores: 16% above FFS.

The authors speculate that insurers achieve greater risk scores through a variety of means:

- They might pay physicians more for higher risk patients, which encourages providers to code more completely.

- They might selectively contract with providers that code more aggressively.

- They might provide electronic tools that pre-populate physicians' notes with prior-year diagnoses.

- They might provide training to physicians' billing staffs that leads to more intensive or complete coding.

- They might review claims, notes, and charts and request changes.

- They might incentivize or require annual exams for "risk assessment," which uncovers diagnoses that might otherwise not be observed.

- They might proactively contact enrollees or send physicians or nurses for home visits, particularly for those expected to have high risk scores.

FFS Medicare would not engage in any of these practices.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services already deflates MA risk scores by 4.91% to adjust for upcoding. Even after this adjustment, MA upcoding costs taxpayers an additional $2 billion per year. The Government Accountability Office believes upcoding is more substantial, warranting up to a to 7% adjustment. The analysis by Michael Geruso and Timothy Layton suggests the GAO is correct.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.