Patterns of opioid use and abuse changed in a big way around the end of 2010. What changed and why?

You may be old enough to recall answers to those questions from my post in February in which I described work by Richard Dart and colleagues. Using a variety of data sources, they found that after an abuse-deterrent form of OxyContin was released in August 2010, OxyContin abuse plummeted and heroin use picked up. Abuse-deterrent OxyContin is resistant to crushing and dissolving, operations that users can employ to achieve a faster, more intense high.

A more recent study, published in April, supports these findings with different data. Marc Larochelle and colleagues, publishing in JAMA Internal Medicine, examined a cohort of over 31 million non-elderly, adult patients with coverage from a large insurer from 2003 through 2012.

They note that the release of reformulated OxyContin was just one of two opioid changes to occur in late 2010. In addition, propoxyphene was withdrawn from the market. (Propoxyphene is the active ingredient in the narcotic pain reliever Darvon and was frequently abused.) Their analysis assesses the independent effects of these two changes on prescribing and the joint effects on overdose, as observed in claims data.

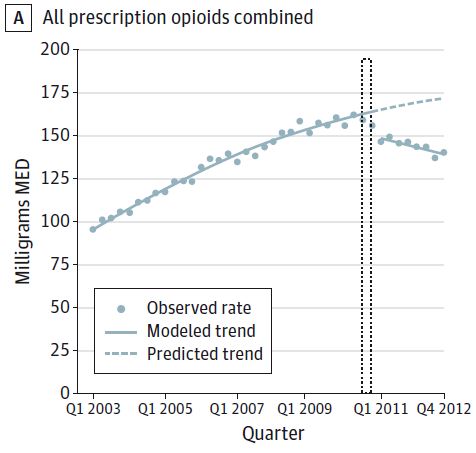

Their effects were substantial and closely coincided with moderation in prescribing of other immediate-release and long-acting opioid medications. The chart below shows the collective impact, and others in the paper tease apart prescribing by agent. (The tall, thin region surrounded by dotted lines indicates the period during which reformulated OxyContin was released and propoxyphene withdrawn. MED = morphine-equivalent dose, a means of normalizing all opioids to an equivalent basis.)

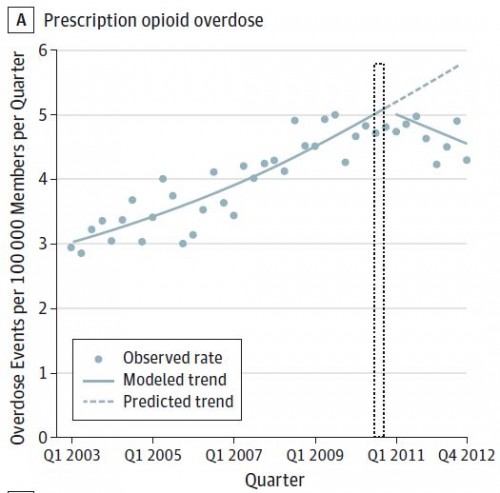

Prescription opioid overdose also exhibits a structural break, as shown in the chart below.

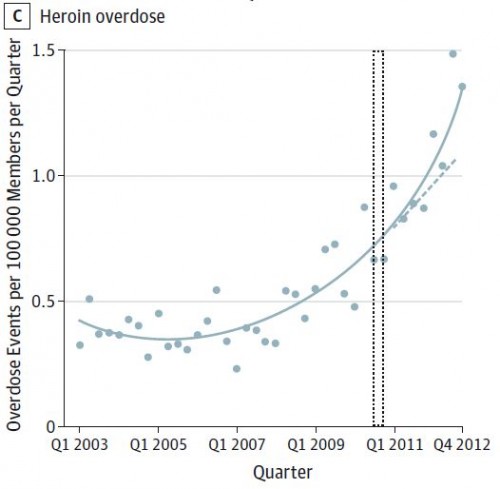

Heroin overdoses, which had been on the rise, picked up steam.

As these results make clear, the authors mention, and as articulated more fully in the accompanying commentary by Hillary Kunins, abuse-deterrent formulations and withdraws of highly abused narcotics painkillers are only a partial solution to the opioid epidemic.

Additional public health policies that promote judicious opioid prescribing can reduce population overdose risk. Judicious use means favoring nonopioid or nonpharmacologic approaches to pain management and, if opioids are used, prescribing the lowest possible opioid dose for the shortest amount of time necessary to control pain. These strategies need to be strengthened along with the introduction of abuse-deterrent formulations of long-acting opioids. Promising public health approaches include prescription drug monitoring programs, pain clinic regulation, insurer and pharmacy benefit manager policies, and promulgation of guidelines.

Finally, there are proven, cost effective (even cost saving) methods of reducing the harm substance use disorders can cause.

To amplify individual health care professionals’ efforts, policy and structural approaches can increase availability and appeal of the full continuum of services, including treatment with effective pharmacotherapeutic agents (eg, methadone and buprenorphine) as well as harm reduction services (eg, naloxone distribution and access to sterile injection equipment).

Yet, as recently shown by Brandan Saloner and Shankar Karthikeyan in a JAMA letter, risk-adjusted treatment rates over the past decade or so for patients with opioid abuse disorder have remained flat.

It's gratifying to see that we can influence opioid abuse, though disheartening to see that when we cut off one avenue, it pops up somewhere else. Something big happened in 2010, but it wasn't enough.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs, an Associate Professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health, and a Visiting Associate Professor with the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.