Last year, on The Upshot, I raised the mystery of why Medicare Advantage (MA) is growing so rapidly.

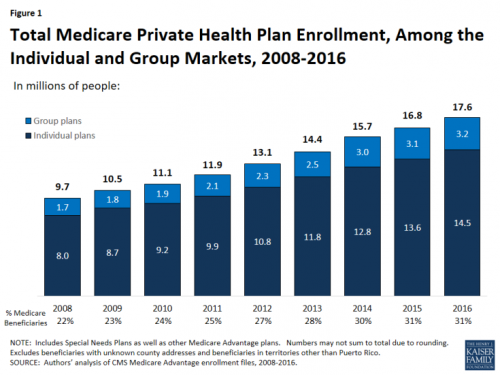

A growing proportion of Medicare beneficiaries are opting out of the government-run insurance program. They are instead choosing a private plan alternative, one of the Medicare Advantage plans. The strength of this trend defies predictions from the Congressional Budget Office, and nobody can fully explain it.

The reason it defies predictions is that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) reduced government subsidies paid to MA plans, relative to their highs in the late 2000s.

Today, about one in three Medicare beneficiaries is enrolled in a private plan — a record high.

Yet, historically, when plan payments have been cut, insurers exit markets and enrollment falls.

In the early 2000s, Medicare+Choice — then the name of what is now the Medicare Advantage program, which offers private plan alternatives to traditional Medicare — was struggling. The proportion of Medicare beneficiaries with access to a Medicare+Choice plan declined from 72 percent in 1999 to 61 percent in 2002. The number of plans offered dropped 50 percent, and enrollment dropped 21 percent. Insurance industry representatives said that the problem was that government subsidy payments to plans were not keeping up with costs.

The program was renamed "Medicare Advantage" and payments increased as part of the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act. Since then, insurer participation has grown, so much so that by 2007, every Medicare beneficiary had access to at least one plan.

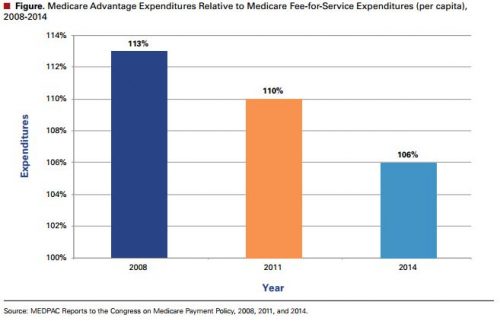

Upon reading my Upshot post, Anna Sinaiko, Research Scientist in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, informed me that her paper with Harvard Kennedy School economist Richard Zeckhauser has a run down of many possible explanations for MA's surging popularity. (The first chart, above, of government MA relative to TM spending per capita is from their paper.)

The authors point to five factors that may explain continued MA growth in spite of the ACA's cuts to plan payments. First, the cuts were less rapid than previous ones—they were phased in over four to six years, depending on severity by county. This gave insurers time to adjust to lower subsidies, perhaps allowing them to stay in the market with different plans rather than exiting the market.

Second, the cuts were tempered by quality bonus payments. They were not as severe as prior cuts, at least not for plans with high quality ratings.

Third, Medicare beneficiaries today have had more and better experience with managed care than those of decades past. Managed care plans of the 1990s, for example, were reviled for their onerous requirements and restrictions. Today, many plans demand little of their enrollees, apart from staying within networks for minimum cost sharing. As such, choosing an MA plan may seem to many like choosing something familiar and not strongly disliked, as opposed to traditional Medicare, which may seem foreign.

Fourth, MA plans have improved, relative to past years' plans. Network extent in today's MA PPOs may be larger than those of past HMOs. Plan quality and consumer satisfaction meets or exceeds that of traditional Medicare.

Fifth, insurers are able to structure MA plans to maximize their attractiveness to consumers. For instance, by keeping premiums low (but, perhaps, making up the difference in cost sharing), plans benefit from consumers bias toward low premiums. Traditional Medicare, in contrast, is constrained to the same basic premium and cost sharing structure it's had for decades. It has no ability to rapidly adjust to the innovations presented by MA plans in the market.

Another factor, not mentioned in the article, may be that employers are dropping or decreasing the generosity of retiree Medicare supplements that wrap around traditional Medicare. As supplements become relatively more expensive or unavailable to consumers, highly subsidized MA plans that largely fill the same gaps may appear more attractive.

These are all the standard explanations for MA's surge that I've heard. One challenge is that few of them are readily testable with available data. Because MA's cost to Medicare is different than TM, predicting MA enrollment is important for projecting future Medicare costs to taxpayers. We've entered an era in which such prediction has become difficult and more speculative.