When Medicare Advantage plans are paid more, how much greater benefit (or lower cost) is passed on to beneficiaries? A recent paper adds to the growing body of work on this question.

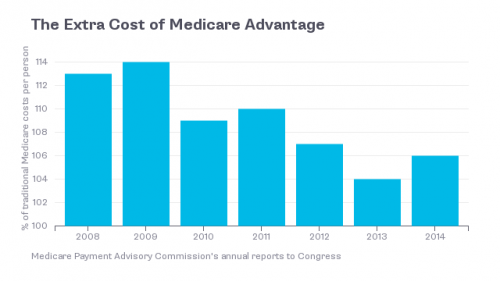

In addition to premiums collected from beneficiaries, Medicare Advantage plans receive taxpayer-financed payments from Medicare to provide at least the basic Medicare benefit to beneficiaries. Much of the debate around Medicare Advantage is how much more the government pays plans relative to the cost of covering a beneficiary in traditional Medicare. The chart below provides the recent history. There's no question that Medicare Advantage plans are paid more than average traditional Medicare costs. The question is, what do they do with the extra money?

Because they can provide the basic Medicare benefit at a cost below that which they're paid, many plans offer additional value to beneficiaries beyond those of basic Medicare. These include reduced cost sharing and extra benefits, like hearing aid or eyeglass coverage.

In a post on The Upshot in July, I summarized the literature on just how much more value beneficiaries receive from Medicare Advantage plans per dollar of additional payment.

[A]t least three studies suggest that for each dollar of these higher payments that plans receive, beneficiaries get only a fraction of a dollar of value. A study by Harvard scholars found that a $1 increase in payment translates to at most 50 cents in additional benefits. Another by researchers from the University of Pennsylvania found that only 20 cents of each additional dollar in plan payment is converted into better coverage. Finally, my own work with my colleagues Steven Pizer of Northeastern University and Roger Feldman of the University of Minnesota found that only 14 cents per dollar of additional payment benefits Medicare Advantage enrollees.

Now there is a forth study in this area. Marika Cabral, Michael Geruso, and Neale Mahoney examined the effects of a change to Medicare Advantage payment rates ushered in by the 2000 Benefits Improvement and Protection Act (BIPA), which raised payments to plans in 72% of the nation's counties. Using a difference-in-differences approach that compared counties where payments went up to those in which it did not, the authors found that 53 cents of each dollar of payment increase translated into benefits or reduced cost sharing or premiums for Medicare Advantage enrollees.

The authors decomposed this "pass-through" of higher plan payments as follows. For each dollar in additional payments to plans, beneficiary premiums fell by 45 cents and the total actuarial value of benefits, reflected in things like lower copays and extended supplemental benefits, increased by 8 cents. So, in total, beneficiaries were better off by 53 cents for each dollar in additional government payment.

Their study also provides several other useful insights. First, they found limited evidence of favorable selection into plans (enrollment by healthier than average beneficiaries). Second, they found that competition in the Medicare Advantage market affected the extent to which higher payments to plans benefit enrollees. In the most competitive markets 75% of plan payment increases were passed through to beneficiaries. In the least competitive markets, only 10% were.

It's this final result that I find to be the most interesting contribution to the existing literature. Competition really matters. Beneficiaries in highly competitive Medicare Advantage markets can, in theory, receive close to the full benefit of each additional taxpayer dollar in plan payment. But no markets achieve that, and, on average, markets are quite far from the ideal. Close to half of each dollar in additional payment from the government is retained by plans, typically.

One of the main arguments in favor of Medicare Advantage is that competition provides the greatest value to beneficiaries. Even if one believes that to be the case, according to this study, Medicare Advantage may not achieve levels of competition to come close to fulfilling its potential. Beneficiaries are supposed to be better off under competition. The less competitive the program, the less clear it is that they are.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.