As we await the case to be heard by the Supreme Court as to whether premium tax credits can be provided to consumers purchasing plans on the federal exchange, let's revisit the role of those tax credits. A RAND report by Christine Eibner and Evan Saltzman, published in October, spells out that role and what would happen without them. (See also this analysis by the Urban Institute.)

Recall that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) offers premium tax credits to consumers enrolled in exchange (aka Marketplace) plans if their incomes are between one and four times the federal poverty level (FPL). At the low end of this income range, consumers contribute between 2 percent of their incomes toward the cost of the second-lowest silver plan, rising to 9.5 percent at the high end. Consumers can pay more if they purchase a more expensive plan or less if they purchase a cheaper one.

The value of such subsidies to individuals is clear: they reduce the price they pay for health insurance, shifting some of it to the federal government. What's slightly less obvious is that these subsidies are valuable even to people who don't receive them: the premium tax credits reduce the price of insurance for everyone.

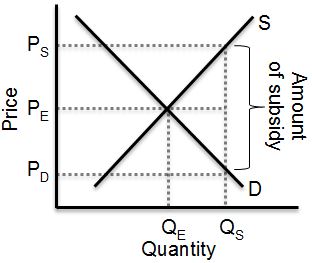

Though true, this is a little weird if you only know enough basic microeconomics to get into trouble. Basic micro teaches us that the provision of a subsidy cannot decrease the price. In fact, to some degree (depending on the slopes of supply and demand curves), it should raise it, along with the quantity bought and sold. This is shown as an increase in quantity from QE to QS and a corresponding increase in price from PE to PS in the figure below, taken from my microeconomics book, coauthored by Mike Piper.

What the figure shows is that, because of the subsidy, though the full transaction price goes up to PS, the consumer only pays a fraction of it: the subsidy reduces the consumer's price but not the total price received by the producer. What the figure doesn't quite show is that the full transaction price, PS, is the same for everyone, regardless of how much subsidy received. That's so unless the supplier of the good can price discriminate based on subsidy (or anything correlated with it, like income). In the market we're talking about — the individual market for health insurance — such price discrimination is explicitly outlawed by the Affordable Care Act's modified community rating provisions. (Premiums can vary by age and smoking status, but only with constraints. Insurers aren't likely to be able to exploit this limited flexibility to effectively price discriminate on the basis of subsidy, if at all.)

Were this an exam, I'd give the foregoing analysis a D. It's correct for most goods, but not for health insurance. What's different about health insurance — and left out of the analysis above — is that its cost changes with the composition of purchasers. A health insurance product's premiums is largely the average health care cost of the risk pool it attracts, plus a bit more for overhead and profit, which we can ignore for our purposes. Rational (or even somewhat rational) consumers compare the premium to their expected costs (those they'd have to pay out-of-pocket without coverage) when deciding to purchase coverage. When premiums go up, healthier individuals with relatively lower expected costs are less likely to buy coverage. (I'm sidestepping the fact that people rationally buy coverage to protect themselves against the risk of catastrophic costs well above those that are expected. But even accounting for that, it's true that, in general, those with lower expected costs are less likely to buy coverage as premium rises.)

Given this, what the Affordable Care Act's subsidies do is pull lower expected cost (healthier) consumers into the market. Those eligible for a subsidy are less price sensitive, since their contribution toward premium (at least that of the second-cheapest silver rated plan) is a fixed percentage of their income. As more healthy individuals buy coverage, insurers' per person costs (claims) come down — the risk pool is said to become more "favorable" — which reduces premiums for everyone in the risk pool, even those who do not receive a subsidy. (For a more thorough, graphical explanation, see this post by Matthew Martin.)

So, what happens when those subsidies go away? The risk pool becomes more "adverse" — it's comprised of relatively sicker and more costly individuals and fewer people overall. Premiums rise. But how much?

To answer this question, the RAND study authors used a simulation model based on the economics sketched above and nationally representative survey data. They found that eliminating premium tax credits would result in a large decrease in enrollment and a sharp increase in premiums due to adverse selection. Enrollment would fall by 68% and premiums would increase by 43%. What's likely to happen under these circumstances is that far fewer insurers would offer plans; the market would not support them. Thus, consumers wishing to purchase individual-market products would suffer two kinds of harms: much higher premiums and loss of choice. (Never mind the additional harms of being uninsured, for those who would otherwise wish to be covered.)

Of course, premium tax credits aren't the only provision that encourages purchase of coverage. So does the individual mandate. However, there is a hardship exemption to that mandate; those for whom the lowest-cost insurance product is above 8% of income are not subject to it. Larry Levitt estimated that 83% of subsidy-eligible individuals would receive such a hardship exemption if subsidies are withdrawn. As premiums increased for everyone, some proportion of those not eligible for subsidies would also be exempt. Thus, though the mandate would still apply, it would apply to fewer people. To the extent that it motivates healthier people to purchase coverage, removal of subsidies has an indirect effect on making the risk pool more adverse.

It is pure speculation how the Supreme Court will rule. What is not speculation is the economic consequences to the new health insurance markets the Affordable Care Act was intended to encourage. They will be large and severe.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.