The Obama Administration is making a strong push to increase access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for addiction to opioids. In this and a subsequent post, I will review evidence of prior MAT access expansion measures.

Treatment for opioid dependence is worth the cost but under-provided. Part of the problem is poor access to programs that offer substitution therapy like methadone or buprenorphine, particularly in rural areas. Policy can help. A 2000 law permitted an expansion of substitution therapy, and a recent study documented a substantial, subsequent increase in access to treatment for opioid dependence.

In 2000, the Drug Addiction Treatment Act (DATA) permitted an expansion of opioid substitution therapy. It did so by providing waivers from the registration requirements of the Controlled Substances Act to physicians so they could prescribe buprenorphine and related substitution treatment medications outside of opioid treatment programs like methadone clinics. Prior to DATA, substitution treatment was only available in treatment programs. In Health Affairs, Andrew Dick and colleagues described the growth in and geographic distribution of opioid treatment programs and waivered physicians who could prescribe substitution therapy, from 2002-2011.

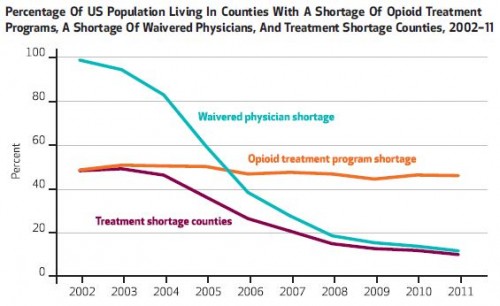

In their analysis, the authors characterized a county as having a shortage of treatment programs or waivered physicians if the number of providers per capita in the county was in the lowest decile among all counties or in the second-lowest decile and had high treatment need. Treatment need "was a function of the number of opioid related overdose deaths, heroin prices, and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics," described in detail in an online appendix. A treatment shortage county was one that had both a waivered physician and opioid treatment program shortage.

The following chart from the paper shows that the percent of counties with treatment shortages dropped from about 50% to about 10% between 2002 and 2011. Nearly the entirety of this drop was due to waivered physicians, not treatment programs, suggesting a strong effect of the Drug Addiction Treatment Act.

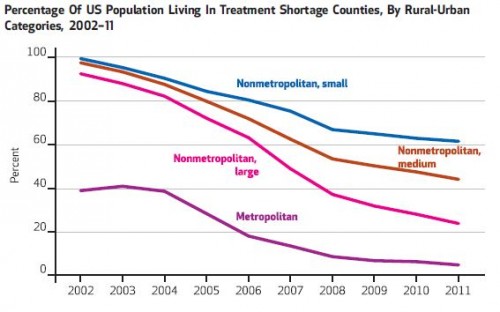

As the following chart shows, reduction in treatment shortage varied by county urban/rural status. More urban counties saw greater reductions in shortages, relative to more rural ones.

Despite these gains in access to opioid substitution therapy, only 2.2% percent of physicians were waivered—and only 3% of primary care physicians—as of 2012. So, there is ample room for greater access, and particularly in rural areas.

Greater access to and care for opioid dependence is at least cost effective and some work shows it to be cost savings. Methadone treatment reduces hospitalization and emergency department use and limits the spread of HIV by reducing the use and sharing of needles. Analyzing New England states, the Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council found that as access to treatment increased so did savings to society, saving money in the long run. New England states could save $1.3 billion by expanding treatment of opioid-dependent persons by 25 percent, the Council found.

This all suggests that the Drug Addiction Treatment Act improved access to cost-effective and even cost-saving care. However, as Andrew Dick and colleagues point out, there are other barriers to access might require further policy development. These include stigma, un/under-insurance, managed care/behavioral health treatment requirements, among others.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs, an Associate Professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health, and a Visiting Associate Professor with the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.