In an August 2015 issue of Annals of Internal Medicine, Kevin Quinn offered one of the most insightful typologies of health care payment methods I've ever seen. Though they can be mixed and matched to some extent, are modified by risk adjustment in many cases, and can go by different names, he identified eight fundamental methods:

Fundamental Payment Methods

- Per time period—e.g., a fixed payment per year; salaried physicians amount to the same thing

- Per beneficiary—a payment method more common to health plans than providers, a.k.a. capitation

- Per recipient—though rare, this is like #2, but it's a carve-out for a specific service a patient might receive, e.g., "a cardiologist

- Per episode—e.g., bundled payments or prospective, diagnosis-based payment (DRGs)

- Per day—a.k.a. per diem

- Per service—it's not evident any entities pay according to number of services

- Per dollar cost—cost-based reimbursement

- Per dollar of charges—"charges" are "costs" marked up for profit (they're higher); typically a payer would pay a proportion of charges, reflecting negotiated discounts or in an attempt to pay costs

accepting financial risk for treatment of [a] cardiac patient"

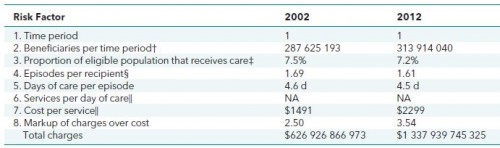

It may not be obvious, but the ordering above reflects a useful nesting of financial risk. Here's how to see that, using inpatient hospitalization and the non-institutionalized U.S. population as an example (familiarize yourself with the table and then I'll walk you through it):

Using actual data (sources listed in the paper) for 2002 and 2012, the table shows number, proportion, or multiplier relevant to the units that relate to the eight types of payment methods, in order. These are interpretable as risk factors in the following way. Imagine there's only one payer of health care for all Americans (call it AmeriCare). And imagine there's just one, giant, U.S. hospital system (US Hospital Corp.). Now imagine AmeriCare and US Hospital Corp (USHC for short) are squaring off to negotiate 2012 payment rates for inpatient care. How would financial risk to AmeriCare and USHC change as the unit (risk factor or payment method) changes? Starting at the top, and with key words in bold that link to the fundamental payment methods listed above, here's how to think about it:

- Obviously the time period unit is one year (2012). If AmeriCare and USHC negotiated at this unit level, AmeriCare would hand USHC a wad of money for the whole year. USHC would have to manage that wad to fund all the inpatient care for all Americans in the year, keeping any surplus as profit and going into debt for any overrun. In other words, USHC would assume all the cost risk. Good luck USHC! (Though different, because the VA is a public agency, not a private corporation, this is similar to the kind of risk VA hospitals face.)

- The number of "beneficiaries" (here, anyone who could use hospital care, not anyone who does use hospital care) per time period is a count of the U.S. non-institutionalized population, about 314 million in 2012. Relative to #1, negotiation at this level shifts very little risk from USHC to AmeriCare, since population size is predictable with high accuracy. Should there be a monstrous epidemic requiring substantially more hospital visits than anticipated, USHC would be in trouble.

- Payment per recipient of that care shifts that kind of risk from USHC to AmeriCare. In 2012, only 7.2% of the non-institutionalized population received inpatient hospital care. Per recipient payment would place the risk in the estimate of that figure with AmeriCare, since it would pay USHC a fixed amount for any, unique recipient of care, no matter how many there turned out to be.

- Each unique recipient of care might visit the hospital for one or several episodes of care in a year. On average, in 2012, a recipient had 1.61 inpatient hospital episodes. So, payment per episode is at a slightly finer level than payment per recipient. Under this arrangement, AmeriCare would assume risk in the number of episodes per recipient, USHC would retain the risk in cost per episode though. Here, Quinn notes that we've reached a dividing line in the risk hierarchy between "epidemiologic risk (prevalence of medical conditions) and performance risk (treatment of medical conditions)." Though one could argue the point slightly, by and large, neither AmeriCare nor USHC can exert much influence at the unit levels above per episode (#1, #2, #3 above), at least not at the time scale of a year; they're mostly baked into the nature of medical conditions. However, at and below per episode (#5, #6, #7, #8 below), the organizations can more easily influence the number of units. That is, payment becomes more contingent on volume. One can even find health policy experts worried about bundled payments' sensitivity to efforts by providers to increase episodes, for example. We've transitioned from concerns about stinting (USHC providing less care than necessary), which are associated with all payment methods at and above episode-based payments, to concerns about waste (USHC providing more care than necessary), which are associated with all payment methods below episode-based.

- An episode's costs can be attributed to days, and each inpatient episode was about 4.5 days long in 2012. Payment per day moves length of stay risk from USHC to AmeriCare. In cases for which the daily rate is above (below) marginal cost, USHC has an incentive to increase (decrease) lengths of stay.

- Each day includes many services. In principle AmeriCare could pay USHC per service (without regard to what those services are). In practice, I'm not aware this has ever been done. More common would be to pay different rates for different services, but that's getting closer to ...

- ... payment per dollar cost of service. If AmeriCare paid USHC its cost, clearly the cost risk is entirely with AmeriCare. USHC has no incentive to control costs. Traditional Medicare's original payment system was intended to pay hospitals their costs. Perhaps that's what many insurers attempt to do today as well but, ultimately, what they're doing is a version of ...

- ... payment per dollar charge, meaning hospitals report their charges and insurers pay some fraction of those. In terms of cost risk and incentive for cost control, this isn't much different than #7. Quinn reports average inpatient hospital markups over cost of 3.54 in 2012, meaning that for each dollar of cost, a hospital receives $3.54.*

There's more to say about this typology. I'll continue discussion of it in a future post.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs, an Associate Professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health, and a Visiting Associate Professor with the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Boston University, or Harvard University.

* By email, the author shared that he computed this markup from HCUP data and found a similar markup in AHA data and Medicare data.