A problem with theoretical arguments is it's often hard to tell how much they matter.

Consider, for instance, how much the economic downturn during and since the Great Recession affected Medicare spending growth. One might theorize that it hardly affected it at all because the vast majority of Medicare beneficiaries are retired, so they shouldn't be affected by rising unemployment rates, and they aren't at risk of losing job-related coverage. Also, even if the economy did affect beneficiaries' financial status, after accounting for secondary coverage and supplemental policies, many Medicare beneficiaries face little cost sharing.

On the other hand, some Medicare beneficiaries work, so the labor market should have some effect. Moreover, the Great Recession affected many people's retirement accounts significantly, possibly reducing the resources beneficiaries might have to spend on health care, not to mention transportation to it. Some beneficiaries may have shifted resources to help other family members affected by the economy. And some beneficiaries—even those with supplemental coverage—do face non-trivial cost sharing.

But how much should all that have reduced Medicare spending? Is the answer approximately "not at all" or "by bazillions of dollars"? Theory alone isn't specific. We need evidence.

Using Medicare, Health and Retirement Survey, and National Health Interview Survey data through 2010, a study by Michael Levine and Melinda Buntin concluded that

the use of Medicare services by beneficiaries has not, on average over the past few decades, moved in concert with the business cycle. In addition, we find no evidence of a relationship between sudden declines in the value of elderly beneficiaries’ assets or their income and their use of health care. We do not, therefore, attribute the difference in spending growth between the two study periods to the recession’s effect on unemployment, lost income, or declines in the values of beneficiaries’ assets.

Recently, in Health Affairs, David Dranove, Craig Garthwaite, and Christopher Ody examined the issue, covering more recent years and at a finer geographic unit of analysis than Levine and Buntin and other work on the question. Dranove et al. estimated the effect of changes in employment-to-population ratio (for <65 year olds) on traditional Medicare spending for non-disabled beneficiaries at the county level over 2004-2012, controlling for county and year fixed effects. The employment-to-population ratio should be interpreted as a proxy for the state of the economy, since it's clearly not a measure of the extent to which non-disabled Medicare beneficiaries (who are all 65+ years old) work.

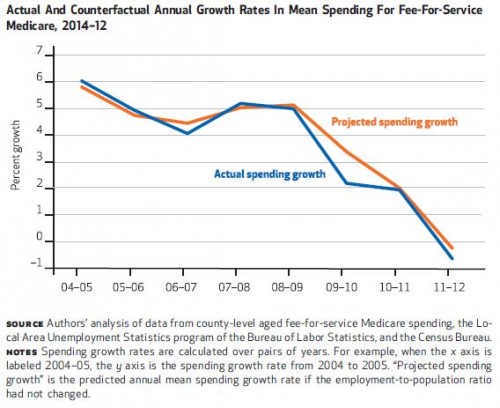

The authors found that a one percentage point decrease in the employment-to-population ratio was associated with a 0.2 percentage point decrease in Medicare spending. Contrast this with results from their prior analysis in which they estimated a 0.8 percentage point decrease for the privately insured, working age population. From 2004-2009, the average annual rate of growth in Medicare spending was 5.1%, from 2009-2012, it was 1.1%, but it would have been 1.7% in the absence of the economic downturn, the authors estimate.

All told, the economic downturn explained 14% of the Medicare spending slowdown between 2009-2012, or about $4 billion. That's about 0.25% of total traditional Medicare spending (excluding Medicare Advantage and Part D).

This estimate fills in some of the gap left by the analysis by Chapin White, Juliette Cubanski, and Tricia Neuman, which found that 62% of the slowdown in Medicare spending since 2009 could be accounted for by policy changes and lower growth in prescription drug prices. Adding Dranove et al.'s estimate of a 14% from the economy, we can explain 76% of the slowdown. The authors' prior work showed that 70% of the slowdown in health spending for a privately insured, working age population was due to the economy alone.

This estimate fills in some of the gap left by the analysis by Chapin White, Juliette Cubanski, and Tricia Neuman, which found that 62% of the slowdown in Medicare spending since 2009 could be accounted for by policy changes and lower growth in prescription drug prices. Adding Dranove et al.'s estimate of a 14% from the economy, we can explain 76% of the slowdown. The authors' prior work showed that 70% of the slowdown in health spending for a privately insured, working age population was due to the economy alone.

One factor left out of the analysis by Dranove et al. is the effect of the increasing enrollment in Medicare Advantage. Their measure of spending was for traditional Medicare only. Medicare Advantage enrollment grew through the recession, and MA plans are paid at a rate that's above average traditional Medicare spending. The price sensitivity experienced by Medicare beneficiaries that explains how the economy affects traditional Medicare spending is also an explanation for growing MA enrollment. MA plans offer coverage of more services for lower out-of-pocket cost.

In any case, the new study's finding that the economy does affect Medicare spending is in conflict with some prior work, noted above. It's possible that differences in years analyzed account for differences across studies. However, even if (or when) a slower economy does contribute to lower Medicare spending, the relationship is a lot weaker than for the working-age, privately insured population.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs, an Associate Professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health, and a Visiting Associate Professor with the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Boston University, or Harvard University.