One, of many, reasons to blog about research is that blog posts can and often do reach a much wider audience than the studies they rely on. A paper by Jenny Hoang and colleagues is a case study that makes this point.

The investigators compared traffic (online page views) to two radiology journal articles and a blog post about them by their senior author, from from April 2013 to September 2014. The articles — both on the topic of incidental thyroid nodule imaging — appeared in the American Journal of Neuroradiology (AJNR) in September 2013 (and ahead of print in April 2013) and the American Journal Roentgenology (AJR) in January 2014 (and, I presume, before then ahead of print as well). Links to both articles were emailed to the journals' email lists. The AJNR was also tweeted and discussed on the AJNR Fellow's Journal Club podcast. The AJR article was selected the AJR Journal Club.

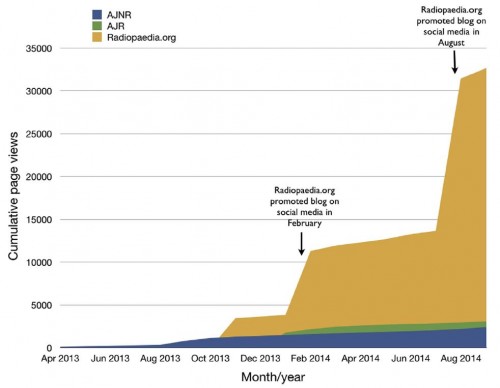

The Radiopaedia.org blog post referencing both the AJNR and AJR articles was originally posted on November 5, 2013, and updated on August 16, 2014. It was shared on Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter to followers of Radiopaedia.org on those social media platforms in February 2014 and August 2014.

Which got more traffic, the journal articles or the blog post about them? You can tell by the title and first paragraph of this post that it was the blog post, right? OK, so try to guess how much more traffic the blog post received. Was it more by a factor of 2? 6? 9? 123?

The answer is 6. The journal articles received a combined 5,478 page views over the study period. The blog post received over 32,675, the vast majority from Facebook. An increase in AJNR traffic is apparent in the chart below in August and September 2014; it was probably spillover from the blog post.

There are lots of reasons why a blog post would get more traffic than a journal article. It's shorter and easier to read. It's free and ungated. In the case of this study, the Radiopaedia.org blog is very popular. Not every blog would garner the same level of traffic. We should also acknowledge that readership volume is a process measure that may not translate into any greater scientific, practice, or policy influence. And, to be fair, the journal articles were also distributed in print. If one accounts for print circulation, the blog's readership was still higher (by how much, the authors did not say).

Finally, this analysis is a case study, so it's unclear how much the findings can be generalized. That said, there are a few other studies to consider, as the authors summarize:

Allen et al found that blogging and social media promotion of 16 selected articles correlated with increases in daily rates of downloads for full-text articles by 3 to 4 times. Shema et al showed that articles that were promoted on a research blog (ResearchBlogging.org) increased journal citations compared with articles that did not receive blog citations. Finally, Thelwall et al found a positive correlation between altmetrics and eventual scholarly citations for >200,000 PubMed articles with at least 1 altmetric mention, compared with other articles published immediately before and after it in the same journal. However, a prospective randomized study recently published in the high-impact cardiology journal Circulation found no advantage for articles promoted via social media versus those not promoted within a 30-day interval.

By the way, Hoang et al. appeared in the Journal of the American College of Radiology, which I do not read. It was brought to my attention on Twitter, an increasingly useful means of sharing studies of interest, at least in my experience. So, now you know not only why some of us blog, but also why we tweet.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs, an Associate Professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health, and a Visiting Associate Professor with the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Boston University, or Harvard University.