As I documented in my previous post, syringe exchange programs (SEPs) reduce the spread of infectious diseases (like HIV and hepatitis B and C), promote drug treatment among injection drug users, and save money. The savings come, in large part, from averted health care spending — treating HIV and hepatitis B and C is expensive — much of which would otherwise be borne by public programs. (Half of people with AIDS are on Medicaid, for example.)

So, on financial grounds alone, SEPs are in taxpayers' interest. This and other benefits of SEPs have been known for decades. Yet, the law prohibits use of federal funds to purchase clean syringes for SEPs, though, as of this year, it does allow support for other aspects of SEPs. Many states and municipalities also restrict SEP operations. On what grounds?

Neil Hunt and colleagues summarized criticisms of drug use harm reduction approaches, including SEPs. Among them, many opponents of SEPs think they don't work or will promote drug use, contrary to the evidence.

It's entirely possible, of course, that some policymakers and segments of the public are unaware of or misunderstand the research on SEPs. But, that's not the whole story. Injection drug use is considered by many to be not just unhealthy but immoral. For this reason, injection drug users, like the broader population with substance use disorders, are often stigmatized. A negative attitude toward them can promote willful misunderstanding or biased interpretation of research on harm reduction of drug use.

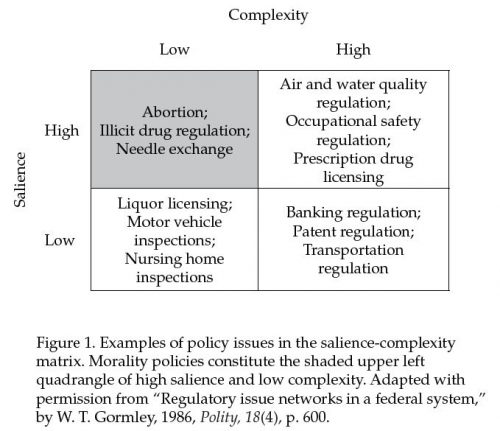

In an insightful analysis of the politics and policy of SEPs, Elizabeth Bowen explained the misapplication and marginalization of research. In doing so, she adopted the framework of William Gormley, which illuminates key aspects of morality-driven politics and policy that differ from, say, economically-driven ones. The framework characterizes policy issues along two dimensions: salience and complexity (see figure below).

SEPs are at the intersection of two public health issues: injection drug use and infectious disease. These have potentially large and feared effects on individuals, their families, and communities. Therefore, they — and SEPs — are salient in a way that, say, the manner in which motor vehicles are inspected is not. At the same time, SEPs are simple — the exchange of used for clean injection equipment. They are readily grasped in a way that, say, patent regulation is not.

Bowen explains that for highly salient and low complexity issues like SEPs, values and emotions tend to dominate over science. (It's the morality, stupid.) From politicians to journalists to citizens, on such issues everyone has an opinion. We both care deeply and we are not confused about what policy is on the table. Why bring evidence to bear when our gut tells us what's right? It's very easy to slip into a "data-free zone." Moreover, when policy is morality, not economically, driven, what does it matter whether it saves money or not?

Morality-driven policies, including those governing SEPs, abortion, the death penalty, and sex education are never settled. Even when a law is passed or a high court rules, the debate goes on. They perpetually garner media attention and are the focus of symbolic legislative action, like passing bills that have no policy impact but serve to "send a message" or to force legislators to pick a side.

Where does that leave research and researchers? Sean Allen, Monica Ruiz, and Allison Rourke documented the role of evidence in SEP policy change in three cities: Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Washington DC. Research was used differently in each case.

Baltimore's legalization of SEPs in 1994 followed, perhaps, the most hospitable policy environment for SEP research. Allen, Ruiz, and Rourke wrote,

Baltimore primarily used research evidence in an instrumental manner to directly facilitate and guide policy change. One interviewee captured this instrumental use of research evidence as follows: “... I think Maryland was able to ... fend off bad stuff and make policy decisions based on science.”

This is evidence-informed policymaking at its best. It doesn't always go so smoothly. Sometimes advocates for change need to use research differently and do more work.

For example, in Philadelphia, policymakers were initially not ready to hear the evidence. So, research played a different role there in supporting legalization of SEPs in 1992. After an illegal SEP commenced in 1991, efforts were first made to change public opinion about it.

Activists accepted that policy change may be best achieved by first changing public opinion about SEPs and then empowering constituencies to put political pressure on legislators to change policy. [...] This indirect, conceptual application of research evidence was illustrated by an interviewee who stated, “... you educate community, then you educate constituencies that eventually pressure politicians or, or vote for politicians."

Though Congress eventually permitted municipal funding of SEPs in DC in 2007, the debate exemplifies how research is frequent misused or ignored on morality-driven issues.

[O]pponents’ use[d] evidence [...] out of context, misinterpreting research findings, or selectively picking language from research articles that they thought supported their claims. [...] Interviews suggested this unwillingness was derived from persons’ fears [...] and based on moral ideologies. [...] “It is possibly the most crazy-making thing about this issue ... [Politicians] [...] saying, ‘I don’t care what the data say, I won’t have it’.”

The lesson for researchers is that their work can make in impact, even on morality-driven issues. But it may require more elaborate application than communicating facts to policymakers. Because elected officials, or those whose jobs rely on them, need simple messages that convey cultural alignment with their constituents, sometimes the culture needs to change before policy can. For some issues, communicating research to broad, lay-audiences may help support the cultural change that's prerequisite to policy change.