Physicians don't want their patients to suffer pain (duh). They don't want them to die of drug overdose either (double duh). The trouble is, opioids prescribed and used to address the former concern too frequently lead to the latter tragedy. Of all drugs for any condition, the class of drug is the most commonly prescribed, with as many as 20% of office visits leading to an opioid prescription. In a December Wall Street Journal article, Dr. Russell Portenoy, a (reformed) champion of the use of opioids for pain management, spoke out about the risks.

Dr. Portenoy's message was wildly successful. Today, drugs containing opioids like Vicodin, OxyContin and Percocet are among the most widely prescribed pharmaceuticals in America. [...] Now, Dr. Portenoy and other pain doctors who promoted the drugs say they erred by overstating the drugs' benefits and glossing over risks. "Did I teach about pain management, specifically about opioid therapy, in a way that reflects misinformation? Well, against the standards of 2012, I guess I did," Dr. Portenoy said in an interview with The Wall Street Journal. "We didn't know then what we know now." Recent research suggests a significantly higher risk of addiction than previously thought, and questions whether opioids are effective against long-term chronic pain.Writing in JAMA, Deborah Grady, Seth Berkowitz, and Mitchell Katz summarize the evidence:

Of the 25 recommendations included in the Opioid Treatment Guidelines of the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine, none is supported by high-quality evidence. Even in the short term, benefits appear to be marginal for most patients. Two large meta-analyses and 1 evidence summary by the American Pain Society outline the evidence of efficacy for opioid treatment of chronic pain. Of note, most of the randomized clinical trials were small, lasted less than 16 weeks, and excluded patients with a history of substance abuse, psychiatric illness, and depression, who are at increased risk for opioid misuse and abuse. In general, these trials report that opioid therapy results in approximately a 30% reduction in pain scores. Effects on functional outcomes are more mixed and the benefits more modest. Finally, most of these trials compared opioids with placebo, not with other active therapies. [Hyperlinks added.]In a separate published letter in JAMA, Dr. Grady calculates that the

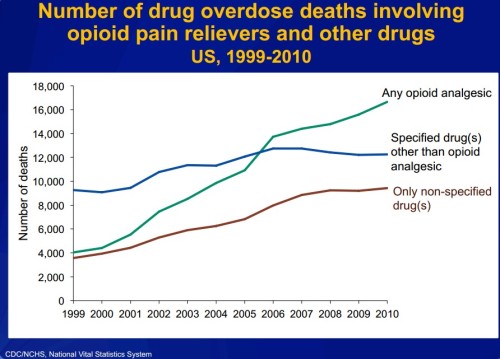

rate of opioid overdose death among these patients [taking 100mg or more of morphine] was approximately 0.3%, or 3 opioid-related overdose deaths per 1000 patients per 3 years—1 per 1000 per year.Indeed, according to CDC statistics, the number of deaths from drug overdoses now exceeds that from motor vehicles. The vast majority of those overdose deaths are unintentional (not suicide), and opioids are the leading agent (PDF).

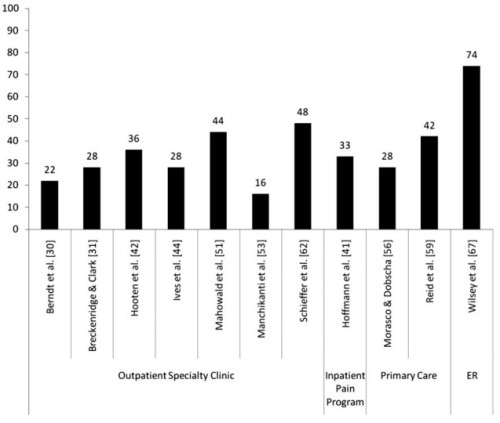

What's to be done about opioids? You can read Grady et al.'s suggestions. I also recommend reading Brad Flansbaum on this subject. One thing I will add is that a substantial proportion of patients prescribed opioids also have or have had a substance use disorder. The following chart is from a systematic literature review on factors and outcomes associated with non-cancer pain patients with a substance use disorder, by Benjamin Morasco and colleagues.

Proportion of chronic non-cancer pain patients who have every had a substance use disorder

What's to be done about opioids? You can read Grady et al.'s suggestions. I also recommend reading Brad Flansbaum on this subject. One thing I will add is that a substantial proportion of patients prescribed opioids also have or have had a substance use disorder. The following chart is from a systematic literature review on factors and outcomes associated with non-cancer pain patients with a substance use disorder, by Benjamin Morasco and colleagues.

Proportion of chronic non-cancer pain patients who have every had a substance use disorder

Patients with substance use disorders have a heightened risk of opioid overdose. At the same time, there is evidence that physicians have a difficult time and even avoid discussing substance use with patients. Given what we now know about the effectiveness and risks of opioids, it would seem that greater attention to patients' substance use history is warranted. It's obviously highly relevant, and the information could save their life.

(By the way, I came across Morasco et al.'s work by way of a cyber seminar series run by the VA's Health Services & Research Development service. The archives are worth perusing. You can register for upcoming seminars here.)

Patients with substance use disorders have a heightened risk of opioid overdose. At the same time, there is evidence that physicians have a difficult time and even avoid discussing substance use with patients. Given what we now know about the effectiveness and risks of opioids, it would seem that greater attention to patients' substance use history is warranted. It's obviously highly relevant, and the information could save their life.

(By the way, I came across Morasco et al.'s work by way of a cyber seminar series run by the VA's Health Services & Research Development service. The archives are worth perusing. You can register for upcoming seminars here.)