Several recent papers have shed new light on the post-health reform experience in Massachusetts. Since the state is about seven years ahead of the nation in implementing a reform very similar to the Affordable Care Act, it's always worth paying attention to new work in this area. However, it should be kept in mind that Massachusetts is different from other states culturally, politically, and economically, so it is never clear how much one can generalize from results pertaining to its reform.

First, let's back up and review some older work. The recent paper by Amelia Bond and Chapin White offers a nice summary of the effect of coverage expansion on access in Massachusetts:

From 2006 to 2010 the percent of the population with a usual source of care increased by 4.7 percentage points, and the percent of the population with a preventative health visit increased by 5.9 percentage points (Long, Stockley, and Nordahl 2012/2013). The percentage of the population with visits to specialists, multiple physicians, and dentists also increased (Long, Stockley, and Dahlen 2012). [A] recent survey also demonstrated decreases in emergency department utilization and in hospital stays. [...]A study by Miller (2012/2013) used the National Health Interview Survey to look directly at office visits, which suggests an increase of 4% in office visits for those aged 18–64 years in Massachusetts relative to surrounding states. Using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample, Kolstad and Kowalski (2012) reported a decreased length of stay and decreased admissions originating from the Emergency Department (ED) in Massachusetts after reform. Their results also suggest that there was little change in the rate of preventable hospitalizations, but that the severity of patients with preventable hospitalizations decreased. Another study by Miller (2012) using administrative data looking directly at ED visits found a 2.4 percentage point decrease in Massachusetts. A number of these results may indicate increased primary care access with patients on average able to access care at an earlier stage.

The one known study looking directly at Medicare beneficiaries uses preventable hospital admissions as a proxy for access to preventative primary care visits and finds no detrimental effect of the insurance expansion on the Medicare population (Joynt et al. 2013). [Links added.]

Bond and White's contribution is based on Dartmouth Atlas and Medicare utilization data:

Principal Findings. In areas of Massachusetts with the highest uninsurance rates— where insurance expansion had the largest impact—[primary care] visits per beneficiary fell 6.9 percent (p < .001) relative to areas of Massachusetts with the smallest uninsurance rates.Conclusions. The expansion of coverage for the nonelderly reduced primary care visits, but it did not reduce the percent of beneficiaries with at least one visit. These results could imply restricted access, increased efficiency, or some blend.

In totality, the evidence of these studies doesn't strongly suggest health care access problems stemming from Massachusetts' coverage expansion. Bond and White's results offer a pessimistic spillover effect, and one we might expect. However, if it's true that Medicare beneficiaries' access to more than one visit decreased as access for the previously uninsured nonelderly improved, it's not a forgone conclusion that's a bad thing in general (though it could be for specific patients). We have underuse (by the uninsured) alongside overuse (by the insured, including Medicare beneficiaries). A redistribution of use from the latter to the former could therefore be efficiency enhancing.

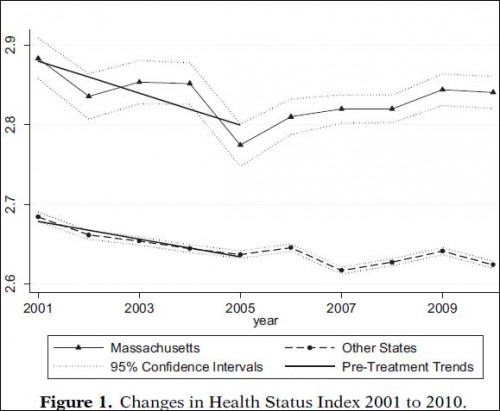

Two other recent papers relied on Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data to compare outcomes in Massachusetts to those in other states, pre- and post-reform. Courtemanche and Zapata (ungated working paper here) found that the Massachusetts reform, relative to other experiences in other US states, was associated with an increase in the probability of individuals reporting excellent or very good health, improvements in self-reported physical and mental health, functional limitations, joint disorders, and body mass index. Though they estimated far more sophisticated, multivariate models, the thrust of their findings is evident in this descriptive chart:

You can read more about the Courtemanche and Zapata study in this post by Ezra Klein.

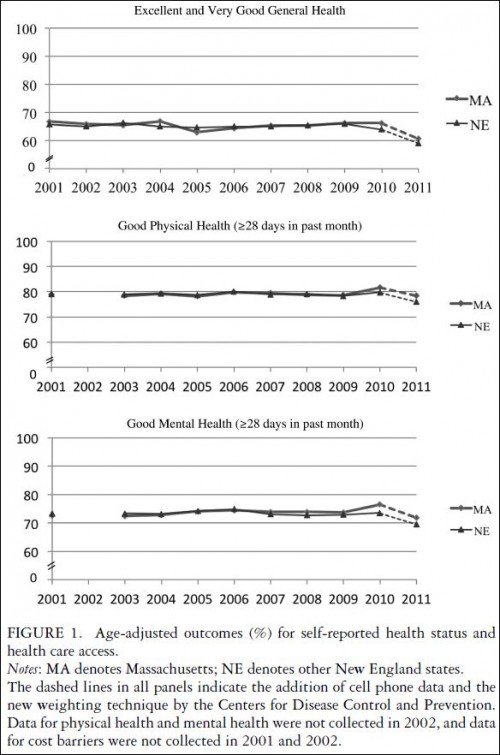

The other recent paper on Massachusetts' health reform and based on BRFSS data is by Philip Van der Wees, Alan Zaslavsky, and John Ayanian. They examined a complementary set of outcomes, finding that, relative to other New England states, the reform was associated with significant relative increases in measures of access and affordability of care, as well as rates of Pap screening, colonoscopy, and cholesterol testing. Again, though they used sophisticated statistical models, you can see the qualitative nature of their results graphically:

Of course, none of this was ascertained by randomized trials. The BRFSS is a survey, and a large one, but one must always add a pinch of salt when interpreting observational studies. It's of some comfort that the results of Courtemanche/Zapata and Van der Wees et al. reinforce each other, are consistent with prior work, and are robust to the many specification variations explored by the investigators. To date, the evidence suggests the Massachusetts reform improved the health of the state's residents.