Many times, I've gone over and over the question of whether and when hospitals cost shift or make up shortfalls in payment from one payer by increasing prices for another. It's worth coming back to because it is not an issue that can be settled once and for all. The conditions for cost shifting can vary as markets change. So, it's good that studies are still coming out. The latest is in the form of an NBER working paper by David Dranove, Craig Garthwaite, Christopher Ody. Any good paper on cost shifting will remind the reader that it is not the same thing as price discrimination, with which it is often confused. Dranove et al. draw a parallel to the airline industry.

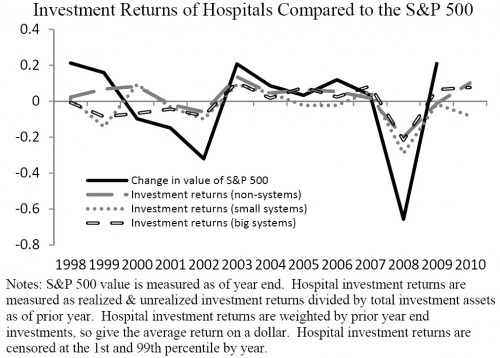

Despite the strong presumption of cost-shifting underlying the arguments for a variety of major health policy initiatives, few convincing studies exist showing that hospitals actually behave in this manner in the modern healthcare market. Certainly, the oft-cited presence of static price discrimination provides little evidence that hospitals engage in dynamic cost-shifting. By analogy, airlines commonly price discriminate between business and leisure travelers, but we would not conclude that a negative shock resulting from the intensification of competition in the leisure segment [lowering prices for such customers] would cause airlines to raise business-class airfares. Indeed, if airlines did raise business-class fares in response to this shock, we would wonder why they had previously declined to exert their pricing power. Instead, we expect airlines to respond in other ways, perhaps by accepting lower profits, reducing quality, or making fewer investments.The argument turns on the presumption that an airline (or a hospital) has already fully exploited its market power. If it has, it can't cost shift. If it hasn't or if it gains additional market power, it can. It's conceivable that some hospitals are not profit maximizers, so, it's an empirical question as to whether they can and do cost shift. Sometimes they may. Sometimes they may not. Of course, we want to know if hospitals can cost shift right now. To find out, we'd love to have very recent downward shocks to public payment (e.g., reduced Medicare or Medicaid prices). Those are forthcoming, but there have been no big changes to exploit in the immediate past. Dranove et al. do something clever, though. They exploit the downward financial shock of the 2008 market collapse. "A hospital would not distinguish between a financial shock caused by Medicaid cutbacks and a shock from some other source, such as a stock market collapse," they write.

Other sectors suffered endowment losses in 2008 too. The authors summarize what happened to art museums and universities. In response, the Art Institute of Chicago cost shifted, raising its entry fee by 50%. Harvard cut costs by instituting a hiring fees and slowing construction.

Other sectors suffered endowment losses in 2008 too. The authors summarize what happened to art museums and universities. In response, the Art Institute of Chicago cost shifted, raising its entry fee by 50%. Harvard cut costs by instituting a hiring fees and slowing construction.

The responses by art museums and universities suggest that if hospitals do not cost-shift, or do not cost-shift by enough to recover their losses, they may respond to financial shocks in other ways. Hospitals might consider a quality reduction, for example through a reduction in staffing. Hospitals may also curtail unprofitable services or charity care. We also consider one response that is not indicative of the “share the gain/share the pain” hypothesis but does have a potentially large impact on patient welfare. Hospitals that rely on internal capital markets may curtail capital investments. During the time period that we study, many hospitals were investing in costly Health Information Technology (HIT) in the form of advanced electronic medical records (EMR). We will test whether hospitals experiencing large stock market price shocks reduced investments in HIT.These are the two fundamental responses to a loss in revenue: cost shifting and cost cutting. (I suppose a third is to reduce profit, to the extent that is possible.) Dranove et al. generally find no cost shifting among hospitals but do find cost cutting. On average hospitals did not raise the prices they charge to private payers in response to endowment losses. However, a subset of high quality hospitals (less than 10% of the total treating less than 20% of all patients) with, arguably, larger untapped market power, did raise their prices. If hospitals didn't cost shift, in general, did they cost cut? Yes, they did. They "decreased large capital expenditures on advanced medical records and curtailed the offering of unprofitable services such as trauma centers and alcohol and drug treatment facilities." These are cuts to quality (or could be), which affects all patients. So, though it my be wrong to presume hospitals cost shift, it is not necessarily wrong to presume that patient welfare could be affected by reduced revenue, whatever the source. They key question is whether hospitals cut (not raise) private prices enough to offset the losses in lower quality. (Price cutting is what a profit maximizing hospital would do.) Another question is whether third party payers pass lower prices (if any) on to consumers. I wouldn't count on it.