We know that patients with more diseases are more expensive and have worse health outcomes. Consequently, almost every observational study in health services research, every health system performance measure, and every payment to third parties uses risk adjustment for comorbidities. The underlying assumption is that patients that are coded as sicker are always, in fact, sicker. That assumption is wrong. That's a substantial problem, one recognized years ago. For example, in 2010, Song et al. found that Medicare beneficiaries who moved to a region with a higher intensity of practice experienced an increase in diagnostic testing and more coded chronic illness relative to those who moved to a region with lower practice intensity. Here, intensity was based on region average spending in the last six months of life. Since it is unlikely that beneficiaries who were about to experience an increase in disease preferentially chose to move to higher intensity regions, this suggests regional variation in coding practices apart from actual variation in prevalence of disease. Think about how troublesome this problem is. If patients are not really as sick as their recorded diagnoses indicate, then risk-adjusted mortality or hospital readmission rates are too low and payments to Medicare Advantage plans for apparently sicker patients are too high. Lots of research is wrong too. Until recently, it wasn't clear what to do about this issue. A recent study by Wennberg and colleagues in BMJ offers a solution. It begins with the recognition that diagnoses come from observation by physicians. Hence, the more doctors you see, the more you're likely to be diagnosed.

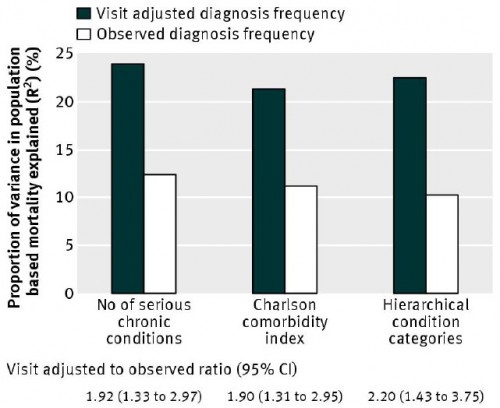

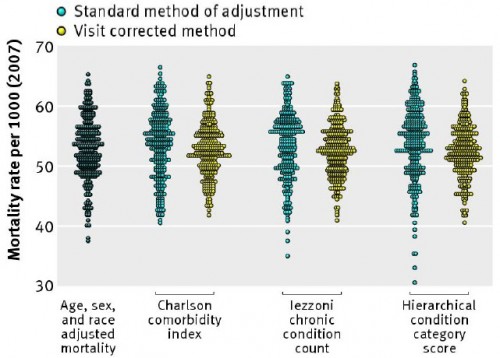

Adjustment methods that depend on the number of different diagnoses recorded in medical records and administrative databases are subject to observational bias rooted in the varying capacity of the local healthcare system: the more physicians involved in care, the more visits, the more diagnostic tests, the more imaging exams, and the more diagnoses and comorbidities uncovered and recorded in the claims data. Adjustment methodologies that assume that a diagnosis made in Miami, Manhattan, or Los Angeles contains the same information as one made in Minneapolis, Seattle, or Salt Lake City are guilty of what one author labeled the constant risk fallacy: the assumption that the underlying relations between case mix variables and outcomes are constant across populations or over time.What's needed is a further adjustment to account for the intensity of observation within a health system. The authors adopt the hospital referral region (HRR) mean number of visits for evaluation and management per Medicare beneficiary in the final six months of life. The strength of this measure is that every such beneficiary is nearly equally sick. They all die in six months time. Therefore, the difference in average visits in the region for such beneficiaries only varies by the nature of the system, namely the intensity with which patients are observed. That's exactly the omitted factor that skews standard, diagnosis-based risk adjustment. As shown in the following figures from the paper, a visit adjusted approach explains a higher proportion of the variance in mortality across several standard diagnosis-based risk adjustment techniques. (All analysis based on a sample of Medicare beneficiaries.) We can't know from this analysis if this approach removes all bias in standard risk adjustment, but it is clearly doing a substantial amount of work.

So, the bad news is that a lot of research, performance measures, and plan payments are biased. The good news is that we now have a way of addressing the problem.

So, the bad news is that a lot of research, performance measures, and plan payments are biased. The good news is that we now have a way of addressing the problem.