The research by Marty Gaynor, Rodrigo Moreno-Serra, and Carol Propper on the effects of hospital competition in the UK is worth knowing about. Their work was recently published in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, though you can find lots of working-paper versions going back several years (here's one). You can also see Gaynor explain the study in the video of this AEI event. Or, you can read this post!

As you no doubt know, the UK's National Health Service (NHS) is nationalized health care, meaning it's not just government provision of health insurance, but the government employs health care providers. It sounds as if there couldn't possibly be any competition in such a system, and, for hospital care, until 2006 there wasn't much. Then a new policy was implemented.

In 2006, general practitioners (GPs) no longer referred patients to a specific hospital, as they had in the past. Instead, as of that date, GPs were required and paid to ensure that patients were aware of five choices of hospital. A new information and booking system facilitated this choice, providing hospital quality data on which patients' selections could be made. Cost data are irrelevant to patients since there is no cost sharing.

However, patients' choices are relevant to hospital revenue. Hospitals are paid a fixed price per patient, based on diagnosis (DRGs). The setup encourages hospitals to compete for patients on quality, at least quality as it is measured and reported. To further promote quality, the NHS conferred greater clinical and managerial autonomy to high performing hospitals, allowing them to reinvest surpluses to further improve care.

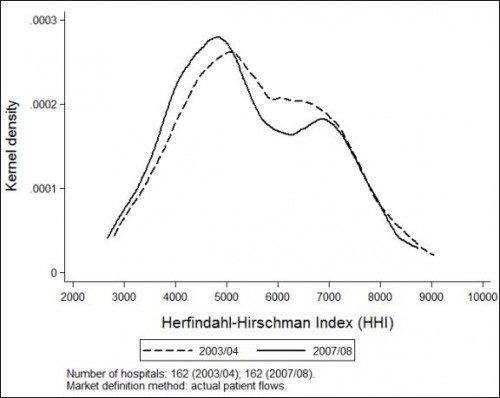

To assess the affect of competition on quality -- and in particular on mortality -- Gaynor et al. exploited the fact that different regions in the UK have different levels of hospital concentration, as measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). A higher HHI indicates a more concentrated market, with 10,000 being the maximum for a monopoly. One of their findings is that the 2006 policy change shifted the distribution of HHI downward, toward less concentrated markets, as shown in the figure below.

The authors also estimated that the net benefit of the policy change is just under a half-billion dollars per year, where they valued the additional life-years gained at $100,000 per year. If HHI could be reduced by one standard deviation (about 1,400), the value outweighs the costs by a factor of five. Those costs come from the additional hospitals that would need to be constructed to achieve the greater level of competition.

Hospital markets in the US are famously concentrated, so this work has relevance beyond the UK. If hospital markets were less concentrated and patients chose hospitals based on quality, perhaps the return, in terms of life years, would also far outweigh the costs. One fly in the ointment, however, is that US consumers have not revealed themselves to be particularly interested in quality data.

I must admit, I'm a bit jealous that the UK has made great strides in improving its delivery system, at least in the way documented by the work of Gaynor et al. Most of the policy debate in the US pertains to how to provide affordable health insurance. Our peer countries have all addressed that issue, though costs remain a concern throughout the world. Having done so, there is more room in the political and policy discourse of those other countries for health system improvement, such as that achieved with more hospital competition in the UK. I look forward to the day when we're able to more fully focus on that as well.

[This post was updated on 12/18/13 to correct the name of the Journal in which the work of Gaynor, et al work first appeared.]