When Daniel Liebman reviewed the literature on the role of health insurance in preventing bankruptcy and financial hardship, he asked if the ACA will "put a dent in the bankruptcy rate." Examining the experience in Massachusetts is a particularly good way to approach the question since its coverage expansion law closely resembles the ACA. Unfortunately, when he prepared the post, Daniel only found one Massachusetts-relevant study.

One study [Himmelstein, Thorne, and Woolhandler, 2011] found that the medical bankruptcy rate did not decline in Massachusetts immediately following its health reform effort, though there could be some confounding due to the Great Recession.

Daniel also pointed out that bankruptcy is only one, extreme measure of financial hardship. Using it to assess financial strain is a bit like using mortality as a health outcome. It's undeniably bad, but so much else bad can happen before one gets to that point.

[M]edical bankruptcy, whatever its “true” rate, represents the tip of a larger iceberg of medical debt and heath care costs in this country.

Examining Massachusetts and using different methods and data, a new working paper by Bhash Mazumder and Sarah Miller (ungated) comes to a different conclusion than Himmelstein and colleagues. The investigators also consider a wide array of financial outcomes, including credit card balances, credit balance past due (over 29 days), fraction of debt past due, third-party collections, credit risk score, and bankruptcy.

The source of data is the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel data set, from which the investigators extracted quarterly data from 1999-2012 for five million and one million individual-year observations in Massachusetts and other New England states, respectively. Their analytic approach is a "triple difference" strategy, probing whether financial outcomes changed more in counties with a higher pre-reform rate of uninsurance as the Massachusetts reform was implemented, relative to other New England states. The results can be interpreted causally under the assumption that

any change in financial outcomes among the more-affected individuals [in higher uninsurance rate counties] in Massachusetts relative to other New England states over the period of the reform is [due to] the reform.

The authors found that

the reform significantly improved credit scores, reduced the total amount past due, reduced the fraction of debt past due, and reduced the probability of personal bankruptcy. We find particularly pronounced reductions in the probability of having a large delinquency of over $5,000. These effects tend to be larger among individuals whose credit scores were low at the time of the reform, suggesting that the greatest gains in financial security occurred among those who were already struggling financially. Furthermore, our analysis yields some suggestive evidence that the reform may have also reduced total debt and the amount of third party collections.

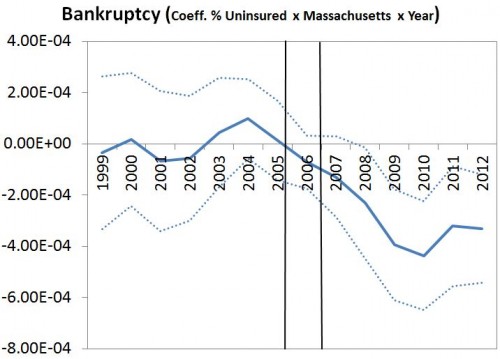

The paper includes many charts such as the following, that illustrate how the coefficient on the pre-reform rate interacted with a Massachusetts indicator changes over time. The vertical lines indicate the period during which reform was implemented. As can be seen below, the reform led to a decrease in the likelihood of bankruptcy. (Dotted lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.) The two-year bankruptcy rate fell 20%. In addition, credit balance past due fell 22%, fraction of debt past due fell 10%, and credit scores rose 0.4%. I recommend downloading the paper for results and charts for other financial outcomes.

The mechanisms by which health reform confers financial protection are several, as the authors point out. First and most obviously, coverage expansion directly decreases exposure to the cost of care for the previously uninsured. Second, more generous coverage (e.g., for those previously underinsured) also offers greater protection against health care costs. Finally, these two effects can spillover to others whose coverage didn't change by reducing the need for them to pitch in when under- or uninsured family members require costly care.

All in all, Mazumder and Miller offer a plausible and convincing case that health reform in Massachusetts decreased financial hardship. It is therefore likely that the ACA will do the same.