Workplace wellness programs--which may include health risk screening, healthy lifestyle, and disease management components--are a big deal: They're a $6 billion industry. By 2012, half of businesses with 50 or more employees and over 90% of very large employers (> 50k employees) had implemented one. Moreover, the ACA includes provisions that encourage them. Perhaps for that reason, nearly half of employers without such a program are considering adding one.

Though, broadly, evidence is mixed on whether wellness programs improve health or lower costs, the methodologically strongest studies are not encouraging that they do either. (A fuller summary of the literature is here.) A recent study published in Health Affairs, by PepsiCo and the RAND Corporation goes a long way toward reconciling the disparate findings in the literature and clarifying how wellness programs may work when they do so.

In 2003, PepsiCo initiated what was to become their Healthy Living program, which included lifestyle management programs (weight, nutrition, and stress management, fitness, and smoking cession) and disease management components (targeting participants with asthma, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, stroke, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, low back pain, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

The Health Affairs-published study sample included 14,555 participants and is based on two baseline years and seven years of experience under PepsiCo's wellness program, making it the longest evaluation of a wellness program to date. The investigators compared wellness program participants to propensity-score matched controls, with matching based on age, sex, being an employee (as opposed to a dependent), geographic region, calendar year, health plan enrollment tenure, total health care costs, emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and comorbidities. Results are based on difference-in-difference regression models.

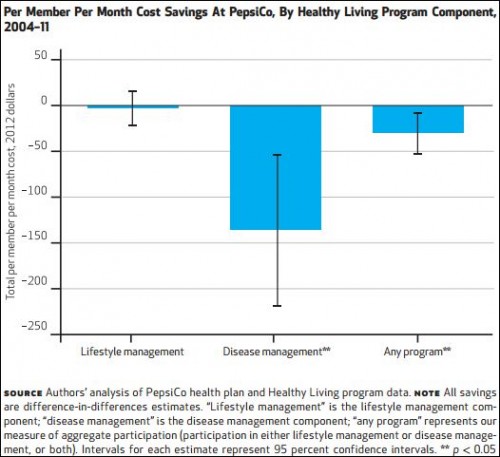

They found that wellness program participation was associated with lower health care costs after the third year, which underscores the need for long-term studies. After seven years, the average annual reduction in costs was $360 per participant. More interesting, however, is the decomposition of savings by program component, as shown in the chart below.

The chart shows that no savings can be attributed to the lifestyle management components of PepsiCo's program. Disease management is where the action is. The authors also found that among disease management participants, those that also participated in the lifestyle management component "experienced significantly higher savings."

The takeaway is a familiar story. When narrowly targeted wellness programs, like many other health interventions, can be beneficial--even cost saving (a rarity among health interventions). But, when more broadly implemented, they often are not. A focus on workers and dependents with specific diseases makes eminent sense. Not only are they the sickest--and in that sense deserving of greater focus--they are the most expensive to insure, offering a far greater opportunity for savings from disease and lifestyle management than a typical insured. A second lesson is that a long follow up time may be necessary to see benefits from a wellness program. Even a two-year study may not be sufficient.

A final caveat is worth noting, as the authors do: This was an examination of one wellness program at one large company. It is by no means clear how readily one could or should generalize to other settings.

If you don't have access to the Health Affairs article, you can read Sharon Begley's summary of the PepsiCo wellness program here and Aaron Carroll's description and commentary here.