Placebos raise ethical quandaries, as highlighted by a PLOS ONE study published last summer. At their heart is the notion that placebos only work if patients are deceived as to what they really are (inert). However, another PLOS ONE study suggests that this may not be so.

To elicit views on physicians' use of placebos, Felicity Bishop, Lizzi Aizlewood, and Alison Adams conducted eleven focus groups, collectively including 58 people residing in England (18 men, 40 women, 19-80 years old). Discussions centered on vignettes presented by the investigators in which placebos were variously prescribed to patients with either a serious or mild condition (terminal cancer or a cold) and with or without deception. The ensuing discussions raised the core ethical tension: should doctors tell the full truth about what placebos are when prescribing them (if at all), or is it OK for them to deceive patients in an attempt to maximize (positive) placebo effects?

This ethical tension rests on two beliefs: (1) To many, "placebo" means "ineffective." And, (2) there is some benefit merely from thinking one is receiving an effective treatment, in the mere expectation of an effect. Therefore, should a physician disclose that she is prescribing a placebo to a patient holding these beliefs, they act to cancel each other out. One can't think one is receiving an effective treatment if one is also told that one is receiving a "placebo," synonymous with "ineffective." (An exception arises if one disbelieves one's physician, but that is probably rare among patients who actively seek treatment.)

The idea that the placebo effect can only be harnessed by physicians who deceive patients is an uncomfortable principle to endorse. Who wants to be deceived? On the other hand, there are circumstances in which employing the placebo effect is the best a physician can do to help a patient feel better (i.e., no other therapy would be more effective). Who doesn't want to feel better?

Not surprisingly, people are torn between wanting to feel better (the consequentialist view) and wanting to preserve control over their care (respecting autonomy). Quotes from the focus groups highlight this tension:

Consequentialist:

"The point is do I get better? I don’t really care how it happens, to be honest."

Respecting autonomy:

"I would be furious, I have to say, if I did go to the GP and wanted – needed medication and [...] then find afterwards that it had been a placebo, without my permission, I would want to sue, I would be so angry."

A few situations dodge the consequentialist-autonomy dilemma. First, when placebos were viewed as ineffective, their use was judged unacceptable by focus group participants. Deception for snake oil and quackery is not OK. Second, some participants thought placebos were a less acceptable use of public and personal resources for minor conditions, like colds, that would resolve on their own. Third, offering placebos to children was viewed as more uniformly appropriate. It was acknowledged that parents do this all the time, with "magic kisses," and the like. Finally, with informed consent, use of placebos in clinical trials was also felt to be appropriate.

Discussion also turned to the possibility of placebo prescribing without deception.

Some focus groups suggested that careful use of language might resolve the dilemma: if doctors are vague or tentative in how they describe placebos then they might be able to use them to elicit placebo effects without directly lying to patients. In other words, some participants suggested that careful wording (or ‘‘fudging’’ the truth) could be a way of avoiding ‘‘blatant’’ lies and thus rendering placebo-prescribing acceptable.

Could this, or even more straight-forward disclosure, ever work? A study by Ted Kaptchuk and colleagues suggest it's possible. They conducted a three-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing an open-label (no deception) placebo (N=31) to no-treatment controls (N=39) for patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The placebo nature of the "treatment" group was disclosed to patients by explaining that it was inactive (an inert substance) like a sugar pill. Further, patients were told that the placebo effect is powerful, that the body can respond to it, a positive attitude helps, and faithfully taking the placebo is critical.

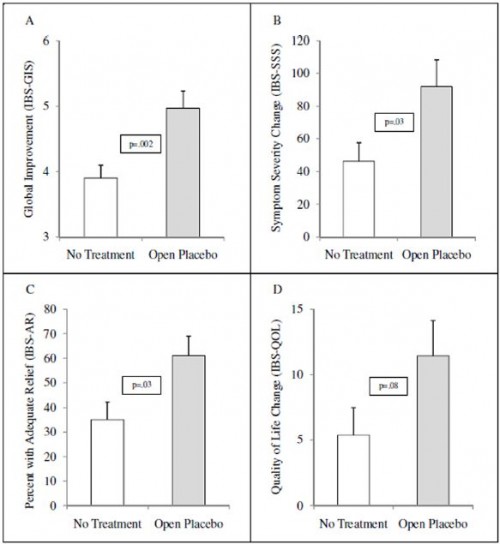

Results after 21 days are summarized in the following figure. In brief, the investigators found statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in various measures of IBS symptoms in the open-label placebo group, relative to the no-treatment controls. (A separate study on depression also found encouraging but limited improvements from an open-label placebo.)

What is unclear from this study is whether the placebo effect would have been even larger if it was closed-label (relying on deceit). However, the authors noted that their open-label placebo response was larger than typical closed-label placebo responses in other IBS studies.

Including use of medications for conditions for which they cannot help (e.g., antibiotics for viral infections), placebos are frequently prescribed. And prior work has found that patients, by and large, don't mind, without much detail on how they think though the ethical dilemmas. The American Medical Association's code of medical ethics advises that placebos be used only if a patient provides informed consent. This could put too much emphasis on autonomy if it completely ruins the placebo effect, under the presumption it relies on deceit.

But at least two studies, noted above, suggest we can have our autonomy and our placebo effect too. This is not enough work to convince me that's generally true, but it's an interesting possibility.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.