With open enrollment coming up for the Affordable Care Act marketplaces, as well as Medicare and some employer plans, I am reviewing the literature on how well people make plan choices. I concluded my first post, which focused on Medicare, with two stylized facts I claimed generalized beyond Medicare: (1) people are bad at choosing plans; (2) providing easy access to cost comparison information makes them better. This post and a forthcoming one back up that claim.

Through a series of six experiments, Columbia business professor Eric Johnson and colleagues directly tested consumers' ability to make rational choices among health insurance plans. Without additional assistance from calculators or the setting of "smart" defaults, they found that consumers are just as likely to select the lowest cost plan as they are to select any other. Moreover, people have no idea how bad they are at this task.

Subjects for the six experiments differed; four focused on a population similar to state marketplace shoppers, one focused on workers, another on MBA students. All respondents passed a test of comprehension of health insurance policies, for instance correctly identifying what a premium, co-pay, and deductible are.

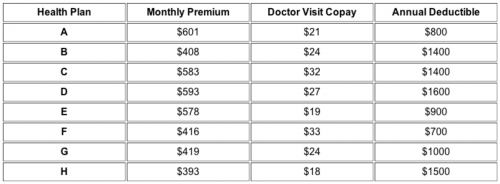

In each experiment, subjects were asked to select the lowest cost health insurance plan from among four or eight options for a family with an anticipated, specified number of doctor visits and out-of-pocket costs over the next year. Though the four or eight options presented varied, the table below shows a typical set of eight selections used in the experiments.

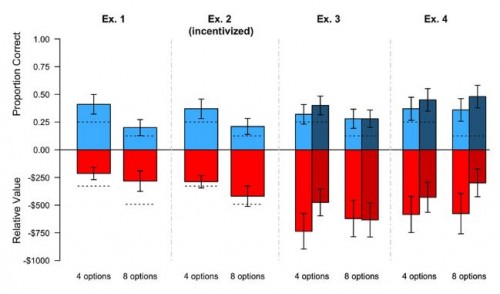

The chart below illustrates results from experiments 1-4 (explained in greater detail below). In the chart, the top half of each bar (in blue) shows the proportion of respondents who correctly selected the lowest cost plan; the bottom half (in red) shows the average difference in total cost (premium plus expected cost sharing) between the selected plan and the lowest cost plan; the dashed lines represent the expected values (proportion correct or average cost difference) if respondents were selecting plans at random. Within each experiment, half of respondents were offered a choice of four plans first, and then eight, the other half vice versa.

Here are how experiments 1-4 differed:

Experiment 1 provided a baseline against which results of other experiments are to be compared. It illustrates that number of options matters. The proportion correctly selecting the lowest cost plan was half the size with eight options than with four (21% vs. 42%), and not statistically different from chance. The annual cost of errors was lower in magnitude than chance would suggest, but still over $200 whether with four or eight plans.

Experiment 2 modified experiment 1 by offering a $1 incentive to participants for making the correct choice in both decisions (among four and among eight plans, separately). Additionally, a correct choice entered the participant in a lottery to win $200. Comparing experiment 2's results to those of experiment 1, we see that these (admittedly, very small) incentives did not appreciably improve decision making.

Experiments 3 and 4 tested decision making with and without a calculator (provision of how much each plan would cost in total). Results with the calculator are shaded more darkly in the chart and are the right column in each pair shown. Though the point estimates suggest the calculator may have been helpful, it made no statistically significant difference in either experiment. A separate analysis showed that participants in experiment 4—all workers—had a much stronger aversion to higher co-pays or deductibles than to to the same additional cost in premium, another sign of irrational decision making.

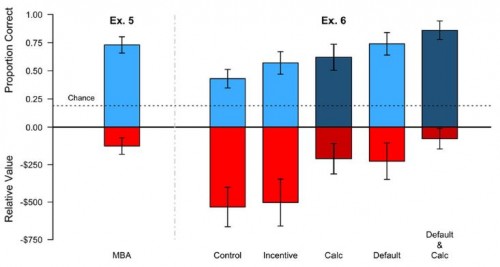

The chart below illustrates results from experiments 5 and 6. Some are much better than those of experiments 1-4. What changed?

Experiment 5's better results can be explained simply: The sample was drawn from a population of MBA students. It seems that MBAs can do things ordinary people cannot.

Experiment 6 offered an educational tutorial to all participants in how to compute plan costs. Five experimental variations were then compared: "control" was the tutorial only; "incentive" was tutorial plus a penalty on participants of 10 cents per $100 in extra costs of their choice; "calc" provided a calculator, along with the tutorial; "default" augmented the tutorial with the lowest cost plan preselected for each individual as the default choice; "default & calc" combined the tutorial with the latter two features. Each of these variations added improvement in performance, and the "default & calc" option finally helped 'ordinary' people perform as well or better than MBA students.

Clearly ordinary people are not good at selecting plans, even among a modest number of choices. Typical ACA marketplaces include many more options: the average consumer can choose from 40 plans. Already, about 11 million people are participating in those marketplaces, with millions more expected to be added in the coming years. If 11 million marketplace participants make plan choice errors about the same size as those suggested above, they are collectively spending $5 billion more than they should.

Clearly people could do with some help. This study suggests that provision of educational assistance (tutorials), smart defaults, and calculators could make a significant dent in that large, collective cost of error, though those interventions would come at some cost as well. But, according to Johnson et al., people don't recognize they need help and probably won't appreciate it if it is provided. In follow-up questions to study participants, they found that

individuals did not realize the need for these interventions. They also did not appreciate the effect of the interventions consistently. [...] All told, the picture that emerges is that of overconfident decision-makers who do poorly and do not realize it, and who do not realize that decision-architecture helped.

This suggests that provision of decision aids may not be enough. People need to also recognize they need them. (Pro tip: Unless you're an MBA student, or similar, you're probably one of them!)

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.