Largely lost in the recent coverage of the general moderation of growth of health care spending is the fact that health care spending growth continues to strain state and local budgets. That's the focus of a recent paper presented at Brookings by Donald Boyd report by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The Pew report notes that states and local governments were partly spared the increasing costs of health care between 2008 and 2010, due to a temporary increase in federal spending on Medicaid. That increase was included in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and extended by subsequent legislation. Despite an increase in Medicaid spending over that period, states' share of it actually declined.

Going forward, however, Medicaid and other state and local health care spending are projected to impose significant budgetary burdens.

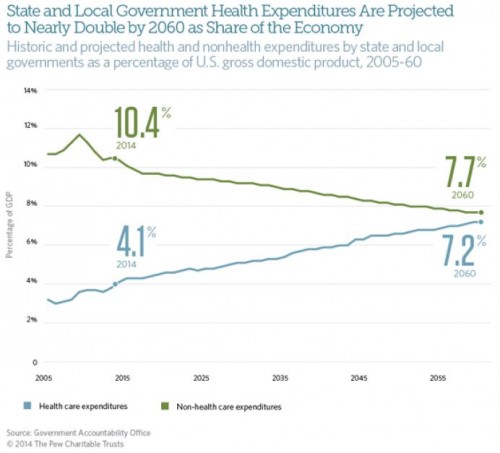

In the years ahead, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services projects that state and local government spending will rise by 49 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars from 2012 to 2022.Looking further ahead, the Government Accountability Office—the nonpartisan investigative arm of Congress —warns that health care spending is the primary driver of the long-term fiscal challenges that it expects state and local governments to face. According to the GAO’s simulation, state and local health-related expenditures will nearly double as a percentage of gross domestic product from 2014 to 2060.

Importantly, Donald Boyd's analysis reveals that the majority of projected state health care spending will not be driven by Medicaid or its expansion.

[State and local health care] cost increases are driven more by non-Medicaid costs than by Medicaid costs. The non-Medicaid increases are driven first by retiree health care costs [] and second by costs of health care for the existing workforce. The Medicaid cost increases are driven primarily by costs for the elderly and disabled. Children, adults, and Medicaid expansion enrollment play a much smaller role in the increases.

All told, future health care spending will take a bigger bite out of state and local government budgets. Consider, for example, the following chart included in Pew's report. It provides historic and projected health and non-health state and local government spending as a percentage of GDP.

Now, it's a bit of hubris to predict trends out 45 years or so. Nevertheless, even from the historic and near-term predictions, the above chart suggests that health care spending is crowding out other state and local priorities. (See also Reid Wilson's summary and comments on the Pew report.)

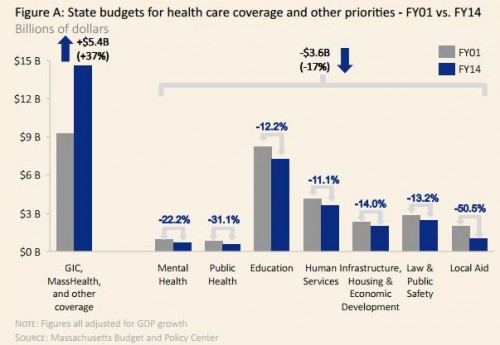

A similar note was struck in the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission’s 2013 Cost Trends Report, in which you'll find the following chart. It shows growth between 2001 and 2014 in state spending on health care coverage on the left and, on the right, spending growth (reduction, really) in other areas: mental health, public health, education, human services, infrastructure, housing and economic development, law and public safety, and local aid. (The health care category includes spending for the Group Insurance Commission (GIC), which provides coverage to state and municipality employees, MassHealth, the state's Medicaid program, and other coverage, like subsidies for private insurance under the state's health reform.)

In Massachusetts, as state spending on health care coverage grew 37% (after adjusting for overall economic growth) over the 14 year period as spending for other areas declined 17% in aggregate. More troubling still, some of those other areas of spending also contribute to health and wellbeing, and perhaps more so than the marginal dollar spent on health care coverage.

Both the Pew report and the evidence from Massachusetts echo the work of Elizabeth Bradley and Lauren Taylor, which suggests U.S. health outcomes lag those of peer nations because we spend too little on services that relate to social determinants of health, in favor of far too much spending on health care directly. (Allan Joseph summarized and commented on this work for The Incidental Economist.) As the health sector gobbles up more of state, local, and national, budgets, this imbalance only grows.

Additional spending on health care to expand coverage may be well worth the state and local spending it will require (see my paper with Aaron Carroll relevant to this), but we would be wise to also consider the merits of that which additional health care spending crowds out.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.