However you feel about reference pricing, the latest paper on the subject by James Robinson, Timothy Brown, and Christopher Whaley is worth knowing about. As Robinson and Brown found in an earlier study, the approach can make a large impact on the market — affecting market shares and prices — at least for specific, elective procedures.

As Nicholas Bagley and I explained, with reference pricing, "insurers set the price they’re willing to pay for a given service or procedure, typically pegging it to a price at which it can be obtained at good quality." Policyholders then pay the difference if they obtain that service or procedure for a higher price. That is, in contrast to copayments for a fixed amount for a procedure, with reference pricing, the policyholder is on the hook for the entire amount (the marginal price) above whatever the insurer pays. That's why it only makes sense for elective procedures for which consumers can conceivably shop and plan, and in markets for which there is ample competition so they can do so.

The recent study considers reference pricing* by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) for cataract removal surgery, which began in 2012. This is in the context of the use of reference pricing by CalPERS for hospital outpatient procedures more generally: it set those prices to those charged by ambulatory surgical centers for the same procedures.

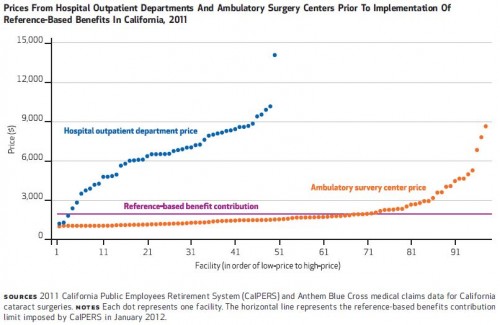

I can see the motivation: the difference in price level between hospitals and surgical centers is stunning, as shown in the following chart (the authors' Exhibit 1). Does cataract surgery really need to cost as much as hospitals charge?

Using 2009-2013 data for non-elderly adults, the authors compared risk-adjusted changes in market outcomes for CalPERS to those for Anthem Blue Cross, which serves the same area (a difference-in-differences design).

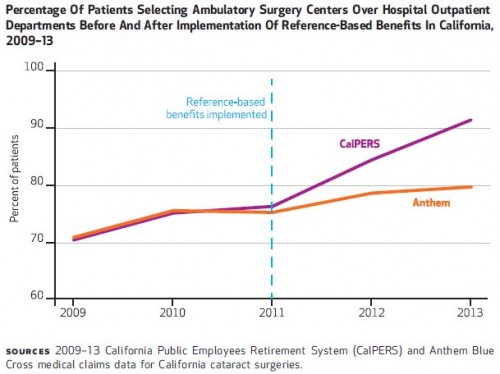

The results are impressive. Reference pricing moved the market, as shown in the following chart (the authors' Exhibit 2).

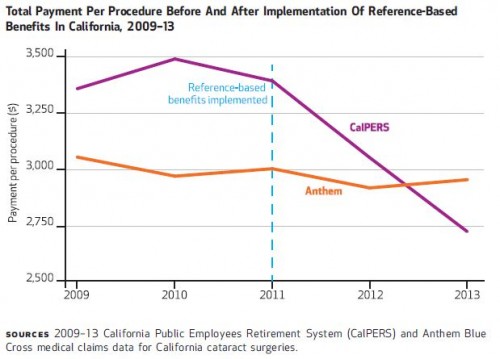

CalPERS payments per procedure plummeted, as shown below (authors' Exhibit 3).

This is consistent with prior work, as the authors explain:

Implementation of [reference pricing] for pharmaceuticals in Europe has been associated with an average 11.5 percent reduction in drug prices and 14.0–52.0 percent reductions in insurer expenditures. In the United States, the implementation of [reference pricing] for inpatient knee and hip replacement surgery was associated with a 28.0 percent increase in market share for lower-price hospitals, an overall 20.2 percent reduction in total payments per procedure, and a reduction in spending by $6 million over two years. [More about knee and hip replacement surgery findings here.]

Though these kind of results may be replicable for other types of care and by other payers, the authors note that not everything is well suited for reference pricing. That limits the impact it could have on the entirety of health spending. One study found that reference pricing might save 1.6% of the cost of seven surgical and radiological procedures. Another found that reference pricing could save, at most 5% across the health system.

Reference pricing has its limitations — about which I've written — but it has also been shown to yield savings, and a lot of savings for certain procedures or medications.

* The authors advocate a new term, reference-based benefits (RBB), because insurers cannot and do not unilaterally set prices. But, they can limit the dollar amount of benefit for a procedure. Since one way to do this is to set that dollar amount to the price paid to a specific provider, it's historically been called reference pricing. For continuity with prior posts, I will retain that term.

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.