The federal Maternal Child Health Bureau (MCHB), under HRSA, released its first “Blueprint for Change: Guiding Principles for a System of Services for CYSHCN and Their Families,” a strategic plan for the care of CYSHCN (pronounced “shin”) in twenty years. CYSHCN are children or youth who have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions and who also require additional health and related services beyond that required for children generally. Nearly 1 in 5 children has a current special health care need, comprising almost 14 million children in the U.S.

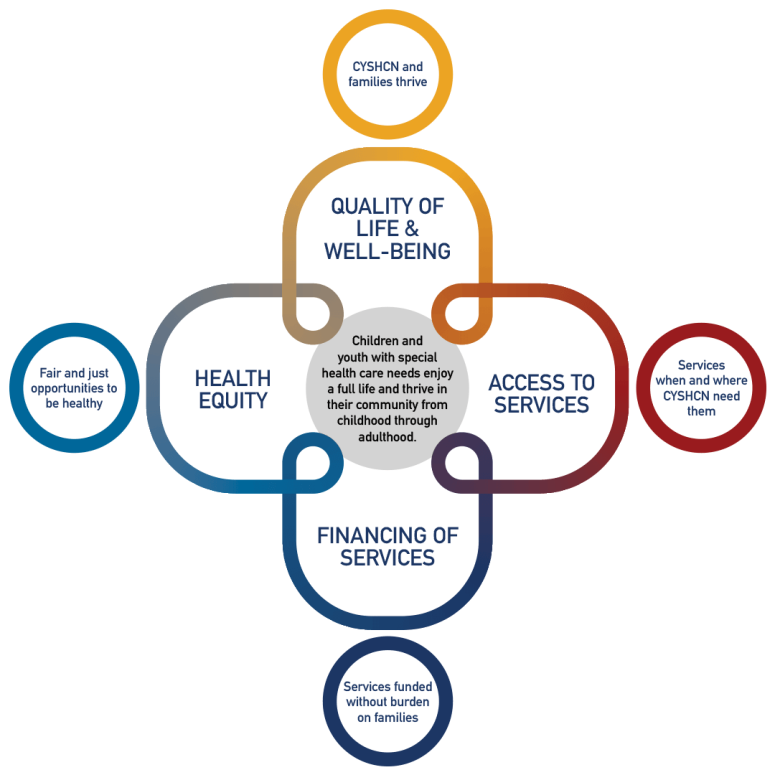

The Blueprint takes a significant departure from the previous plan by calling for structural improvements to the systems of care for these children while still seeking to achieve the six core outcomes of previous plan (early and continuous screening, medical home, families as partners, adequate insurance, community-based services, and transition to adulthood). These improvements are articulated in four interlocking critical areas – health equity, quality of life and wellbeing, access to services, and financing of services.

The Pediatrics supplement documents the challenges, and in many cases the lack of progress in improving outcomes for CYSCHN and their families. It also highlights the challenges of improving equity for this population. HRSA/MCHB surveys families on an annual basis to understand the processes of care (National Performance Measures) and outcomes (National Outcome Measures) as a benchmark of progress. An analysis of the population of CYSHCN and some of these measures is featured in the supplement. Despite some improvement, important gaps remain.

- The percentage of children who have special health care needs that have a medical home (one of the six core outcomes, minimally defined) is 43 percent. Only 15 percent of CYSHCN receive care in a well-functioning system that meets all six criteria.

- The well-being of children and families of CYSHCN is lower than that of their neighbors. Sixty-eight percent of families of CYSHCN report their child is flourishing compared to 85 percent for families of non-CYSHCN children. Parents of CYSHCN report lower resilience and more difficulty coping.

- The financial burden or worry of families creates “job lock” to avoid losing insurance coverage that is twice as high at all income levels as families without CYSHCN. Adequacy of insurance is also worse for those families at higher incomes than those eligible for the more robust Early, and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) Medicaid benefits.

But having documented the challenges faced by these families the Blueprint and its four companion articles offer a plan to move our country out of the doldrums and into a place of forward progress. These supplemental articles written by teams representing diverse leadership in the MCH space highlight equity, access to care, outcomes for families, and financing of services. Each article proposes specific aspirational, but achievable recommendations for the next decade.

The financing of services article points out that the care of CYSHCN is an investment, not a cost. The authors specifically propose that all CYSHCN have an opportunity to be covered by Medicaid on a sliding scale, an opportunity that now only exists for those children with needs significant enough to achieve a disability status. The financing recommendation includes an acknowledgement of the need for better financing of Long-term Services and Supports (LTSS) and of primary care to support care coordination and the medical home. Investments in community-based programing are recommended.

The health equity article points to the even greater disparities experienced by families with CYSHCN who are not white. Families of CYSHCN of all races and ethnicities are more likely to live in poverty that their neighbors without CYSHCN. The authors call for addressing upstream systemic and structural factors that such as racism, ableism, and poverty and downstream design and structure of systems and programs that could reduce disparities.

The authors of the access article further elucidate the challenges families face in finding adequate and integrated care. The article points to the need for the health care systems to adopt an adaptive, responsive system built around the needs of children and families, not just a diagnosis or treatment protocol.

Finally, families led the development of an article focused on family/child well-being and quality of life. While acknowledging that families were integrated throughout this effort, this contribution focused on the need to measure what matters to families, not to the health care system. The Blueprint calls for an expanded effort to measure and act on outcomes that are meaningful to families and children.

Woven throughout the supplement is the need to transform measurement systems so that measures can be effectively used to improve care. Measurement for families must move to outcomes avoiding the pitfall of spotlighting a process (albeit easy to measure) vs. the impact of care on the children and families. Measurement across systems (e.g., kindergarten readiness) and timely return of data to providers to improve outcomes (e.g., linked birth records and claims data) are also called for in the recommendations. Disparities must be adequately measured to create a focus on improving equity.

The goals of the Blueprint for Change are achievable and a path for action. Federal and state policy makers will need to determine that providing care for this population of children is an investment the nation needs. This will take a determined new focus at both the state and federal level. Most importantly Medicaid and Title V must renew and expand their commitment to joint collaboration on service systems and quality improvement. By unlocking the potential of these children, all of us – the children, families, communities, states and our nation – could soar.