As part of an annual, systematic survey of American mayors, the Menino Survey of Mayors, our team at Boston University asked mayors about the key health challenges of their communities as well the health issues for which constituents hold them accountable. We then analyzed mayoral attitudes in the context of current municipal-level health metrics. Our findings were released in June in our new report, Mayors & the Health of Cities, supported by Citi and The Rockefeller Foundation. Here's what we found:

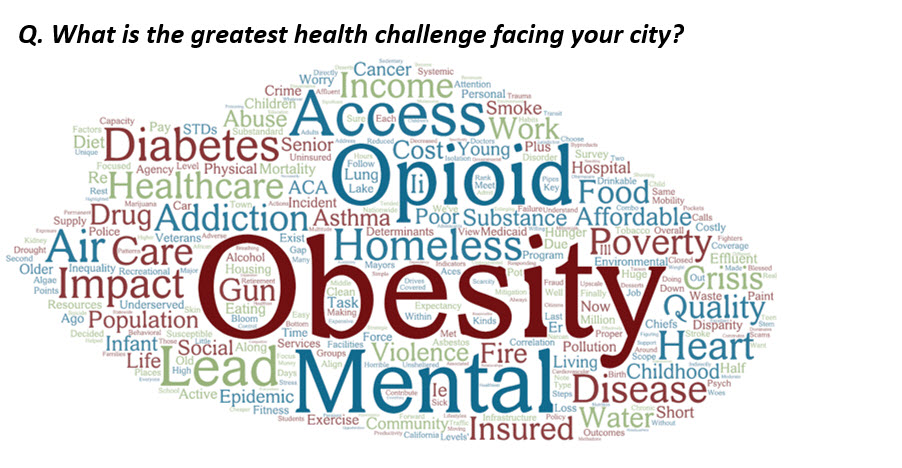

Mayors see obesity and other chronic diseases, opioids, and access to care as the leading health challenges facing their community. Issues related to obesity were the most commonly cited challenge, with 25% of mayors referencing obesity, diabetes or heart disease. A similar percentage referenced addiction, with most citing the opioid crisis as their greatest area of concern.

Mayors believe constituents hold them accountable for a very different set of issues, with traffic crashes, gun violence, and lead and other toxicants topping the list. In response to a close-ended question, nearly three quarters of mayors cited traffic accidents as the health issue for which they are held most accountable, while a little over half cited gun violence and a similar number referenced lead and other toxicants. Obesity emerged as the issue for which they feel they are held least accountable.

Mayoral perceptions differ by gender and party affiliation, with Democratic mayors and women mayors expressing a greater sense of accountability on key health concerns. For example, women mayors feel more accountable for hunger and malnourishment (60% very or somewhat accountable) and mental health (45%) than male mayors (42%, 26% respectively). A higher percentage of Democratic mayors feel more responsible for gun violence (72%) and hunger and malnourishment (55%) than Republican mayors (23%, 32% respectively.)

The prevalence of a particular health challenge in a city predicted mayoral perceptions of accountability in opioid-related deaths, but no other outcomes. The higher the rate of opioid overdose deaths a particular community experienced, the more likely mayors of those cities are to believe their residents are looking to them for action. We examined a range of additional health concerns, from the rate of traffic fatalities to the rate of obesity, but determined that the local prevalence of these issues was not associated with mayors’ perceptions of accountability.

How might the public health community influence mayoral attitudes and actions?

- Frame public health in the context of city livability and vitality. Community health and well-being is integrally related to core functions of a city, from housing and economic development to public safety and air quality. These social and environmental determinants are priority areas where mayors commonly have resources and authority to effect change. A mayor’s annual State of the City address is typically a reflection of mayoral priorities and planned investment, and provides insight into the issues and language that may resonate in a particular community.

- Enlist city officials as peer influencers. Public health researchers are often advised to serve as direct spokespeople via op-eds, testimony or public forums, but sometimes the best messenger may instead be a well-informed city official. Second only to their staff, mayors say their peers are their main source of policy ideas as they eagerly borrow ideas from one another. Forums where mayors and other local officials gather are important avenues for knowledge dissemination. Hundreds of mayors attend bi-annual conferences hosted by the US Conference of Mayors, and both mayors and city councilors convene regularly via the National League of Cities. Professional organizations for relevant municipal officials also abound, including the International City Managers Association, the National Association of County & City Health Officials, the Public Housing Authorities Directors Association, the National Association of City Transportation Officials, or the Urban Sustainability Directors Network. While their events may be closed to non-members, it is important to consider how to equip those who can attend, so that they can elevate effective evidence-based policies amongst their peers. It can also be useful to invite representatives from these organizations into your own gatherings, to gain insight into the issues their members are prioritizing.

- Create multi-city campaigns and pledges. Public pledges and compacts can play a valuable role in enlisting mayoral support at scale. The Trust for Public Land’s 10 Minute Walk Campaign is designed to get mayors – now numbering upward of 270 – to publicly pledge to develop new parks until all their residents live within a half mile of greenspace. Mayors Against Illegal Guns, which is both a network of mayors and an advocacy organization, engages more than 600 mayors in critical, health promoting work. Our in-depth study on city to city networks and compacts revealed the important role that these types of issue-specific coalition-building efforts can play among mayors, amplifying their work, creating a peer group united around a common cause, and connecting their own community’s actions to a broader movement. They also help mayors signal their priorities and may contribute to greater accountability, in part by offering constituents a mechanism to hold mayors to their commitment.

- Engage and empower citizens as health advocates. Mayors in the U.S. are elected officials, beholden to voters for their jobs. They earn that voter approval in part by listening and responding to constituent priorities, which means empowered and well-informed citizens can be critical advocates for local public health priorities. And because mayors live in the communities they serve rather than commuting to a distant capital, constituents can have direct interaction and influence. Indeed, mayors have told us that public events, informal community interactions and neighborhood meetings – in other words, direct engagement - are the top three ways they hear from constituents. A well-informed and organized electorate can advance public health priorities in their community, whether by calling attention to a public health crisis, shining a spotlight on the needs of their neighborhood, or advocating for necessary funds.