America suffers from communities challenged with poor health whose citizens mainly access safety-net hospitals, many of which are failing. Yet, safety-net hospitals have a valuable opportunity to integrate economic development, neighborhood planning, and investments targeting the social determinants of health (SDOH). Wellness Villages (WVs) embody a model where soon-to-be obsolete or insolvent safety-net hospitals are systematically transformed into mixed-use facilities. WVs are communities of varying scale created at the intersection of neighborhood planning and community health. Through the coordination and integration of investments and services such as enhanced primary care and job training, they endeavor to improve health and wellbeing, and generate economic growth. With deep-rooted issues of racial injustice and economic inequity in the aftermath of George Floyd and the peri-pandemic period, the time for radical action is now. By promoting primary care and expanding SDOH investments, WVs can improve the quality of life and enrich the vitality of neighborhoods for residents while protecting their heritages and histories by retaining an anchor facility that’s integrated into the fabric of the community.

The Model & Examples

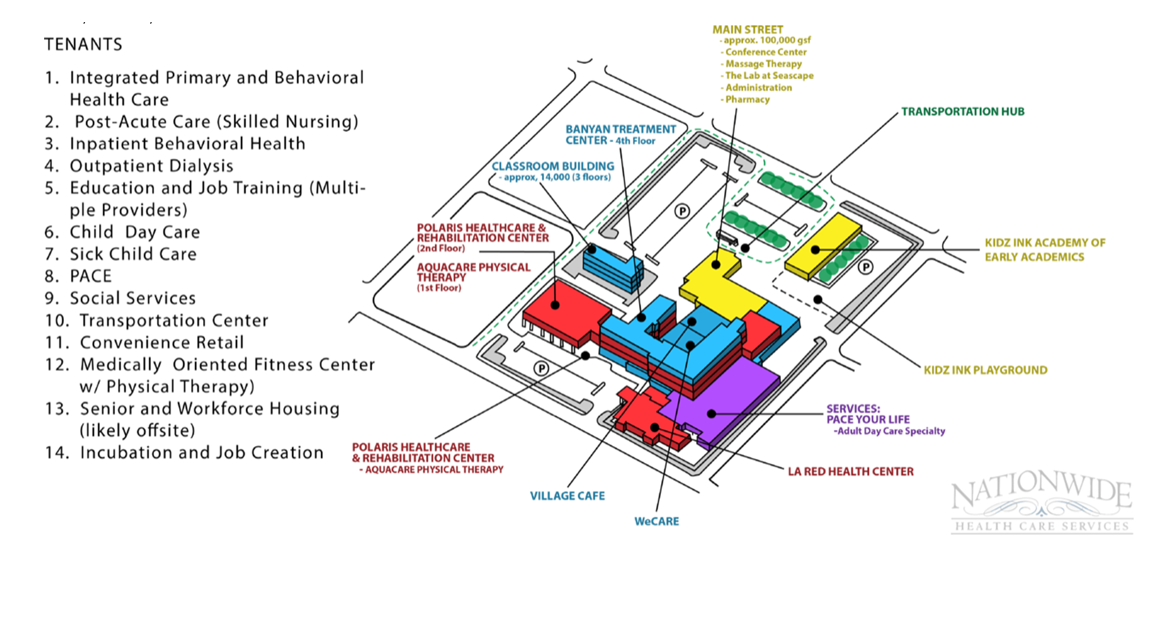

WV partners collaborate to improve health and reduce costs while spurring economic development and neighborhood revitalization. Like a shopping mall located in the transformed hospital, purposefully selected tenants may include integrated primary and behavioral health care (possibly a Federally Qualified Health Center), education and job training, post-acute care, a Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, child and adult day care, and convenience retail. This model counters our hospital-centric system with one emphasizing population health via first-class primary care and SDOH investments. WV’s are also sufficiently flexible to continue to provide critically needed emergency room services and beds. Suitably designed WVs can meet the needs of the population as it is configured today with economic development and attention to large SDOH deficits, including a focus on multiple disparities.

In Milford, DE, a former hospital building now accommodates over 15 different tenants for a fraction of the cost of new construction (see Exhibit). The uses can be categorized around the concept of supportive housing and supportive services – each impacting different SDOH dimensions. The downtown, located within walking distance, benefits from increased employment in the transformed hospital.

In Reading, PA, a WV transformation feasibility study was conducted in 2003 for St. Joseph Regional Medical Center’s two inner city properties as it was planning a replacement for its inner-city flagship hospital. The St. Joseph Regional Healthy Community Initiative transferred the legacy St. Joseph Hospital to the Reading School District. That transfer attracted a $100,000,000-plus state grant for the transformation of the property into a new junior high school. Based on the transformation plan, the School District reutilized the older legacy hospital buildings. Building on the success of this provisional work, the community is pushing forward with a city-wide WV plan.

Rationale

Hospitals close frequently but never because health-related services become unnecessary or because the community has suddenly witnessed economic growth. Providers decide to build a new facility in the wealthier suburbs or leave the area entirely. For these and other reasons, the safety-net hospital era, with roots in faith-based charity, is ending. Poor patient outcomes and finances (largely a function of poor payer mix), and deficient innovation demand new care models while transforming obsolete spaces. Many hospitals (especially rural) risk closure and COVID-19 has sped their decline with estimated losses of $53-$122 billion. (Largely due to better payer mixes, non-safety-net and suburban hospitals, and academic medical centers, are shielded from these forces.) Safety-net hospitals are also disadvantaged by the movement toward expanded price transparency (with low penetration, their commercial prices must be dramatically higher to subsidize their public payments), value-based reimbursement, focus on SDOH and disparities (brutally highlighted by COVID-19), and economic distress. WVs use these facilities to provide what the community truly needs: economic development via job training and service provision responding to severe SDOH deficits.

There are various explanations for disappointing progress toward value-based reimbursement and inadequate public health investments. Governance and management structures that serve the disadvantaged often protect the status quo and fight the transformation to value-based care in challenged communities. Indeed, community hospital boards have varying fiduciary responsibilities, hindering their strategic initiatives.

WVs have inherent public good attributes. They should encourage collaborative, locally designed solutions to needed infrastructure and social service investments to attack SDOH deficits and structural racism. Accordingly, WVs may be super-charged using a Collaborative Approach To Public Goods Investments (CAPGI) process, e.g., to secure integrated transportation.

Challenges

WVs face three operational challenges plus a fourth bearing on their long-run sustainability.

Capital. WVs require capital to finance repurposing of the obsolete hospital into a vibrant economic facility. Financing partnerships can promote WV tenant occupancy below pre-determined costs, challenge communities to match funding, and introduce underwriting by a financial institution with experience in community-impact investing. There are substantial opportunities given current funding devoted to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investing accounting for one-third of total assets under management as of November 17, 2020. WVs also increase prospects for attracting philanthropy to complement tenant rents.

Health. WVs are specifically developed to improve the health and wellbeing of the community yet manifold unmet social needs create intense barriers. Meeting these needs must begin with primary care as studies repeatedly show that despite inordinately high health care spending in the U.S., primary care is shortchanged. Accordingly, WVs demand 21st century primary care: value-based, technologically sophisticated and integrated with behavioral health, chronic disease management and urgent care. With unprecedented venture capital, several companies are positioned to deliver on this goal.

Governance. One way or another, existing boards of trustees likely failed these facilities and their communities. New governance and management practices are required for the safety-net hospital owners, while managing the new WV businesses with novel processes, e.g., creation of 501(c)(3) organizations that extend priority to the health and economic needs of the community. Governance should aim to increase public health investments, decrease health care spending and lower disparities. Visionaries who might lead this revolution include members of religious congregations who, like their founders, are willing to embrace Loonshots, forward-thinking health system executives, double bottom line for-profit companies, and others.

Evaluation is vital to institutionalize a sustainable model. Difficult as evaluations are with single-factor investments, multi-factored initiatives that combine health and economic development are more complex. Nonetheless, there are efforts to develop metrics, examples of measuring social return on investment, and organizations devoted to developing and evaluating models like WVs.

Improving Population Health

Emerging from a once-in-a-hundred-year pandemic is hope of addressing longstanding U.S. health system problems. Americans can become healthier, and COVID-19 could save medicine. WVs should become integral to health care delivery and this model follows the futuristic prediction of the end of the general hospital and even a breaking of the cost curve.

Policies to promote WVs could take many forms, e.g., requirements that affordable housing developments have tie-ins to health care provision or an Accountable Health Communities Model that subsidizes components of WVs. Also, in January 1, 2023, the Rural Emergency Hospital Model might stimulate the conversion of hospitals into WVs.

When a hospital closes, residents have not miraculously become healthy. Typically, it is the converse, a poor population with chronic health care needs leading to an adverse payer mix and hospital financial deterioration. The cure is enhanced primary care and SDOH investments. For roughly twenty years, experts have urged more attention to health promotion and melding public health and medicine. For thirty-plus years, researchers have stressed targeting factors beyond medical care to improve population health (see notes 16, 17, 19 and 22 here). WVs face substantial challenges, perhaps most trenchantly, health leader fidelity to old operating ways. Yet we believe they are worth pursuing since they embody fundamental changes in city and town planning which could revolutionize health care delivery and health.